-

Mulaney’s new special ‘Sack Lunch’ is his best gift all year

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneWait! Wait! Whoa! Have either you or a loved one assembled a list of the best TV of 2019 yet? To judge by the sheer number of these things, surely someone in your household must have written a Top 10 TV list in the past six weeks. OK, so you have? Well, then I am sorry to inform you, but you’re going to have to do it again: Arriving too late for November deadlines of many journalists, but right on time emotionally, Netflix has dropped “John Mulaney & the Sack Lunch Bunch,” a children’s variety show, and it’s almost unsurprising the Chicago comedian’s special would arrive on Christmas Eve.

This year, he’s been the gift that keeps giving.

His “Bodega Bathroom” musical on “Saturday Night Live” was a spring highlight (and a kind of sequel to his great “Les Miserables” sendup “Diner Lobster” from the previous fall); September brought a third season of “Big Mouth,” a very funny animated show he makes with Nick Kroll; last winter had “Original Cast Album: Co-Op,” Mulaney and Seth Meyers’ sendup of Stephen Sondheim for IFC’s “Documentary Now!” series; then there was his voice acting as radioactive swine Peter Porker in the Oscar-winning “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,” his left-field Henry David Thoreau for the Apple TV-Plus series “Dickinson,” his recurring role on HBO’s “Crashing” as a cruel, vindictive John Mulaney.

And still “John Mulaney & the Sack Lunch Bunch” is his best present of the year.

And his warmest. Presented as a show created by adults for adults but starring children, it does what Mulaney does best: Affectionate, quizzical parody, delivered blunt and sweet. He doesn’t acquire targets but memories. Here the inspiration is low-budget, high-energy children’s public TV of the ’70s and ’80s — “Electric Company,” “Zoom,” “3-2-1 Contact.” On a soundstage filled with kids, wearing a white V-neck sweater that wouldn’t look out of place in his native Lincoln Park, he says he recently watched kids’ TV and was not impressed; also, he says he has no children or plans to have children.

What follows is lovingly, decidedly uneven, though like the best of Mulaney’s writing, aware of the limitations and uncertainties. A child asks him to explain the show’s tone.

Well, he says, he made it “on purpose,” and if it’s bad they can say it’s ironic, and if it’s good, you know, thanks, we worked hard on this. Which brings him to his first lesson: if you pretend you know what you’re doing then a lot of people will believe you do. He says he knows many successful people who do the same. “Name names,” a child asks.

“Sister, I could for hours,” he says.

From there it’s musical numbers and sketches and animation and even a little shadow puppetry. Yet the genius here is not in layering an adult sensibility over kid’s material; it’s not in recycling that low-rent TV condescension of where kids say the darnedest things.

Rather, it’s in recognizing the fresh eyes and unique voice in the looseness of a young perspective, in the unwillingness to play by rules but instead invent new ones on the fly. One girl asks Mulaney to play restaurant and takes the role of hostess, then she informs him that they are closed for a private party and SIR! SIR! You’ll have to return another night! Corny as this sounds, it’s a salute to the freedom of those distinctive sensibilities.

Which, the older you get, the more you tend to tramp down and conform until, one day you wonder — if you’re lucky and self-aware enough — what did you sound like again? Which, I guess, makes this seem somewhat like an empowerment seminar for adults. Except Mulaney is too fond and respectful of these kids and who they are to steer their messages. He opens the show with a boy who speaks in a heavy lisp and torrent of sentences, saying he is scared of asteroids but mostly, he’s mostly afraid of drowning. Other kids tell Mulaney they’re afraid of clowns and dying in their sleep and The Purge.

The film? Mulaney asks.

No, the idea, a boy says.

The Sack Lunch Bunch are smart and like a lot of kids, they’re weirdos — and thank God for the weirdos, Mulaney seems to say. Children, in general, are wonderful weirdos. One of the show’s many (and memorable) musical numbers is about a boy who has “tried all the food” but only eats one thing: a plate of noodles (the tube kind, with a little bit of butter). Another number finds a girl struggling to put on a show in a living room full of indifferent adults — until David Byrne, every weirdo’s best friend, arrives. (Incidentally, if you’ve wondered what David Byrne would look like dressed as Elsa, look no further.)

There are so many surprises I hate to give more away. Mulaney’s songs are so memorable that, after the Sondheim parody and “SNL’s” Willy Wonka bodega-bathroom sketch (“Come with me and you’ll be/In a world of zero sanitation”) — all of which featured Mulaney’s songs — you wonder if he’s either a nascent Sondheim himself or just an astute satirist. He’s polite and cutting, tearing into Broadway conventions, but as a way of celebrating whatever unique qualities makes the creakiest cliches sing.

Mulaney, a bad actor and a perfect comedian, is unable here to hide delight on his face; despite what I’ve written, he’s not looking to make a unified theory of how his sensibility works. He’s looking for laughs. That said, “John Mulaney & the Sack Lunch Bunch,” a holiday surprise, comes as close as anything Mulaney’s done to explaining his appeal and outlook. It ends with the Sack Lunch Bunch saying that they fear the loss of their parents’ love, and the loss of their parents, and the loss of goodness in the world, and as each says this in his or her own way, the effect is touching. You are the gift you give others, Mulaney is saying, so remember that: Be confident, use your voice and own it.

“John Mulaney & the Sack Lunch Bunch” will air on Netflix starting Dec. 24.

This story was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on Dec. 27, 2019.

-

There’s magic in a Schiller Woods water pump, or so many Chicagoans, for generations, have wanted to believe

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneAmericans believe.

We believe in democracy, opportunity.

Some believe more than others. But then, some also believe vaccines are not safe (about 28%, according to a recent Wellcome Global Monitor survey). Polling during the 2016 presidential election found almost 50% of Americans believe Iraq was hiding weapons of mass destruction. And ideology is not always a predictor of belief: A majority have long felt that the JFK assassination was not the work of one man (61%, says a 2013 Gallup poll).

Politics aside, some 14% of Americans also believe in Bigfoot, according to a 2013 poll conducted by the left-leaning Public Policy Polling firm of North Carolina; this same poll found that 7% of Americans still believe the moon landing was faked, while 9% insist that fluoride is being added to their tap water for dark and nefarious reasons.

Which brings us to the water pump in Schiller Woods.

It’s a hand pump, just south of West Irving Park Road, near Cumberland Avenue.

There’s nothing conspiratorial about it, and if you know the pump I’m referring to, you need no directions: For you, there is only one pump, only one source of water in the Chicago area worth discussing. You believe in this pump. Perhaps your parents swore by it — as did their parents. Indeed, a very unscientific survey of the people using the pump — conducted by me, every now and then since June — found about 75% of people taking water from this pump believe there is something extraordinary about its qualities and/or history.

“At home, I drink nothing but this,” said John Butryn, who lives on the Far Northwest Side. “No soda, nothing artificial. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ll drink my water like a fish.”

Morning, night, winter, fall, spring, summer — someone is usually at this pump.

Actually, quite often, there is a line of someones, entire families even, shouldering milk jugs and carrying crates of water bottles, waiting to bring home many gallons of what flows out.

Meanwhile, across Irving Park Road, on the north side of the street, a short walk away, is another, very similar pump. Most of the time, though, it sits silent, unloved and little used.

Mieczyslaw Wrobel, 65, carries his jug filled with well water from a pump in Schiller Woods East. (Camille Fine / Chicago Tribune) Because that pump is not this pump.

And this pump, the one on the south side of the street, the one with nonstop parade of regulars, the one with the mystique and community of believers, has meant a lot of things to a lot of people, for generations. It was installed in 1945 to serve picnickers, just another of the hundreds of water pumps erected in the forest preserves of Cook County. Today, there are about 300 pumps, yet only this hand pump needs to be serviced with some frequency.

“My grandmother brought us here all the time when we were kids,” said Letta Kochalis of La Grange Park as she filled several jugs with her sister, Mary Berchos. Both are in their 70s.

“People say it has a specific taste, and that it’s not like other waters. And it’s not. It’s the best water in the world! You’ve heard it’s magic, right? I don’t know if it is, or if it has the rejuvenating qualities they say. But I don’t try other pumps. I hear the pope blessed it.”

I heard that several times.

Ask those who swear by this pump to explain why this pump, and you hear a lot of things: You hear it tastes better than tap water, it keeps colder for longer, it contains holistic qualities, it’s good for heart and teeth, it’s unfiltered and therefore not chlorinated or fluoridated. They note how important a pump like this is in 2019, at a moment when the White House is seeking to roll back clean water restrictions and the Flint water crisis still looms large. They say they simply don’t trust their government agencies with their tap water.

Then once they are done being pragmatic, some of their voices go low and get whispery and they say with a wink: The water from this pump will keep you young an unnaturally long time.

They’ve heard it’s a fountain of youth.

They’ve heard the water comes from a reservoir originating in Michigan, running beneath Lake Michigan, all the way here, a mile and a half from O’Hare. They’ve heard, no, the water actually comes from a spring in Wisconsin. They’ve heard no, no, no, the water comes from Lake Huron. An assistant superintendent of maintenance for the park told the Tribune in 1957 that he believed (mistakenly) the water originated in Lake Superior. I was told by a middle-aged man filling his Jeep with jugs that he heard the water is really a mistake, an unintended tributary that connects to a vein of pure water secretly maintained by wealthy North Shore families. And also, yes, I was told, by many, that the pope himself blessed this pump, in 1979.

Mieczyslaw Wrobel, 65, fills his jug with water from a pump in Schiller Woods East. (Camille Fine / Chicago Tribune) “Holy water” — that’s what they call it.

One woman from Peru who didn’t want her name in the newspaper said that she had been told the water comes out of a remarkable stream of holy water, flowing out of Michigan.

She added, it’s a nice story, she realizes it sounds improbable, yet she wants to believe.

For the record, to play the wet rag of reality: In 1979, 40 years ago this week, Pope John Paul II did visit the Northwest Side of Chicago, but his motorcade stayed primarily along Nagle and Milwaukee avenues and the Kennedy Expressway (and barely slowed down). There is nothing to suggest — from newspaper accounts to official itineraries — that the pope set aside the time to bless a single hand pump. Indeed, the Forest Preserves of Cook County maintains there is nothing supernatural or even that special about the pump or the water it delivers. They have been explaining this for many years. They have heard the stories.

According to Chip O’Leary, deputy director of resource management for the preserves, topographically speaking, the pump sits on 500 acres, some of it oak woodlands, with a bit of prairie and savanna thrown in; the soil is alluvial, typical of fine-grained soils coming out of the Des Plaines River. Tom Rohner, the preserve’s director of facilities — he oversees the pumps — said it’s simply well water, that it comes from an aquifer 85 feet below the surface, that it’s not treated, that it’s not a natural spring (which bubble up regardless of pumps), and that it’s tested quarterly for contaminants (and comes back clean every time).

Also, that neglected pump across the street?

It pulls from the very same well water.

It’s the same water.

Of course, if there were a conspiracy to keep Cook County’s fountain of youth a state secret, that’s what the Forest Preserves would want you to think — right!?! To be certain, I ran a sample of the pump’s water through a $30 home-testing kit, and here’s what came back: The pump’s water (compared with Chicago tap water) is quite low in copper, and very low in iron; its pH is on the high end of the scale; and its alkalinity is low. In keeping with a lot of well water, it is very hard when compared with tap water. Which means, it’s high in minerals and would contribute somewhat to nutritional recommendations for calcium and magnesium. (Incidentally, if you’re wondering, the village of Schiller Park doesn’t get its water from the forest preserves but from the city of Chicago, which filters its tap water from Lake Michigan.)

How does it taste? My first swig was a bit sulfuric, with a faint rotten-egg smell, though the longer the water remained in my bottle, the better it tasted; in fact, within a few hours, the smell faded entirely and the water, stored at room temperature, stayed cold even a day later.

And yet, my middle-aged legs still hurt, my joints still ache. I don’t feel younger.

I suspect it would test low for supernatural influence.

Rohner said the only thing remarkable about the well is its followers, its devoted community of regulars, and the constant lines standing at it. He said tests of its water come back almost identical to tests of other nearby wells in the preserves. He said he started in his job about a year ago and spoke to the person who had it just before him and decided: “There is no justification for (the water’s legend). It’s history, it’s belief, it’s folklore and family history.”

“But I’ll tell you,” he added, “whenever the handle breaks, we’ll get a call in five minutes flat.”

The pump looks out on a large field.

It is slick with grease and clacks and groans. There is no sign directing you to it. The forest preserve once erected a sign noting that usage of the pump was limited to 10 gallons, but that’s a losing game. Now there’s just a notice not to the feed wildlife that wander in from the surrounding meadows. The pump sits at the end of a long path, which is shoveled in the winter. During spring rains, pumpers hold umbrellas high for their fellow pumpers. The stream of customers feels endless. One car pulls away, two pull up. A grandmother with grandson fills six mayonnaise jars; a jogger fills a water bottle then jogs off. An old man wearing his work uniform pushes a hand truck stacked with large office water jugs; he fills each then loads them into his trunk. Chris Berndt, a University of Illinois at Chicago graduate student, rode up on a scooter and filled several small bottles. He told me he has been coming here for two years, partly because he doesn’t trust the fluoridation treatment in tap water.

I also meet a lot of first-generation Polish, many from nearby Portage Park.

They say the pump reminds them of spa waters in Poland. They say they heard about the water from other immigrants, soon after arriving in Chicago (and many have been here 30 and 40 years). They always say the person who told them about it lived to be very old. They say its water makes great ice, superior tea and healthier plants. Some say, having grown up under communism, they prefer to get their water direct, sidestepping officially treated water.

Marian Wlodarski of Norridge placed a branch beneath a jug, steadied the spout, lining it up with the tap then began pumping. “This feels like home,” he said as he worked. “A lot of Polish, we knew pumps like this in Europe. It’s not magic. The pope didn’t bless it. My wife uses it (to pickle) cucumbers. It’s not magic — that’s fake news! But this water is better than other waters.”

Who needs evidence when you have belief?

Jane Risen is a professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. She has studied magical thinking. She notes there is tenet of psychology that instructs, when something seems wrong, a person should take measures to correct. “There is the quick way of responding that we use all the time, and the slower, deliberate process, and those two responses explain a lot. But partly they miss situations like this, where I think some at this pump land. We can be of two minds about a thing we recognize is not rational. Especially when the costs (of belief) aren’t too high and it comes with a sense of community.”

Elizabeth Osika, at 70, in a long flowered skirt, carried large clear jugs to the pump and started filling, then, with the help of other pump regulars, she carried each back to her car.

She did not stop. She worked an assembly line of jugs efficiently and chatted nonstop, “I don’t know if this water is magic or healthy or not. But the water that flowed out of mountains in Poland tasted like this, and I have been drinking this water for 20 years now and I am not dead. Nobody complains about this pump — it’s the only place on Earth nobody complains!”

She filled her last jug. I said, next time if there’s a line, there is that pump across the street.

“What?” she shouted. “That pump! The water is bad there, it smells bad. I’m sticking here.”

This story was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on Oct. 4, 2019.

-

‘To people, they’re a nuisance,’ but to Jim ‘Mothman’ Steffen, the insects are the key to saving a 100-acre forest in Glencoe

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneJim Steffen, the Mothman of Glencoe, the champion of McDonald Woods, a Chicago Botanic Garden ecologist for the past 30 years, as well as the co-author of such must-reads as “Interactions of an Introduced Shrub and Introduced Earthworms in an Illinois Urban Woodland,” brushes the drizzle from his face and crams an umbrella handle into the ground.

Beside it, on a milk carton, rests a device that Steffen constructed not long ago. It resembles a tiny lighthouse, and should you happen to be a moth, that’s exactly what it is. It’s intended as a beacon, to guide you through the surrounding McDonald Woods, luring you closer to its glow in an otherwise dark forest, at which point, should you turn to escape and bonk your bug noggin on its plexiglass frame, you will tumble into the maw beneath the lamplight.

He’s studying the moths of McDonald Woods. He believes that he can help restore these small woodlands alongside the Botanic Garden to something like pre-settlement Illinois. And he believes that its moths, one of nature’s least appreciated pollinators, could be the key.

So, for the past few years, he’s been gathering as much information as he can on what species exist in these compact 100 acres of Glencoe (not to be confused with another, larger McDonald Woods that’s part of Lake County Forest Preserves). He takes his traps out every week or so, from about the first thaw of spring to the first snow of winter. He would do it more often but he’s coming across new species every two weeks, and he doesn’t want to stress out the moths or do any more damage to the population than his intrusions have already done.

That said, if you are a moth, and live in McDonald Woods, Jim Steffen has your number.

He’s currently at No. 596.

Meaning, he’s identified 596 species of moth here, with at least 50 more waiting to be ID’d and cataloged. He’s caught large moths and micro moths. He’s caught black moths and white moths, moths that look copper and moths that look paper. He’s caught moths resembling bees and moths he describes as “mountain ranges with six legs.” He’s caught moths from elsewhere — Central America, Florida — though the majority are native to right here. He’s caught the Toothed Brown Carpet and Splendid Palpita, the Coffee-Loving Pyrausta and Morbid Owlet, the Black Duckweed and Pale Beauty, the Large Mossy Glyph and Common Pug. He’s caught moths as orange as NCAA mascots and moths that look like hairy tongues. He’s caught moths with 1950s TV antennas for antennas and moths with wingspans that zip up as quick and tight as window shades.

Just after Labor Day, Steffen, 68, moves quickly across McDonald Woods, stalking through its thigh-high grasses, stepping over its thin creeks. He carries 40 pounds of batteries on his back. He’s trailed by two younger Botanic Garden employees. He plants a trap, connects the UV light to a battery, tests sensors for brightness, then rushes silently to a new spot.

These moth specimens were collected by Jim Steffen in McDonald Woods. (E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune) Midsummer is peak moth season here, but moths are present year-round, however dormant and Steffen doesn’t expect his weekly catch to plummet for another few weeks. A week earlier Steffen brought back a sizable 400-moth catch. He plants a Botanic Garden umbrella (spray painted gray, to provide camouflage) into the dirt then considers the forecasted direction of the wind and adjusts the canopy (to keep the collection bin from swamping). He says, “It’s sticky and humid right now. It should be a good night.”

People don’t get moths, people don’t like moths.

Steffen leads walking tours of the woods. When he points out the moths, he gets blank stares. “To people, they’re a nuisance,” he says. “They’re pests, people don’t want them around. Because people don’t know about them.” Bees may be pollinators, but so are moths (as are, surprisingly enough, lemurs and flies). “In terms of pollination, moths have never been the industry that bees are known for,” said Mark Metz, an entomologist with the United States Department of Agriculture who studies moths. “Moths are hard to identify, and many moths only fly at night. They’re not well understood. But they play a bigger role (in pollination) than we give them credit. Some new thinking even suggests butterflies are just highly evolved moths — which a lot of butterfly fans don’t like to hear.”

The moth is such a reliable pollinator that Steffen is not even studying the moth to save the moth. For decades, quietly, dutifully, he’s set his sights on McDonald Woods itself.

“My goal is to increase its native diversity as much as possible — plants, animals, insects — and have it all function at a high level,” he said. “So, more predators and more pollinators. The moth survey tells us if that diversity has been increasing or decreasing.” Because many moths (as caterpillars) feed on one or two native plants, they’re telling indicators of woodland diversity. (Basically, the more species of moths present, the more diverse the woods.)

He lays his last trap and stands.The health of McDonald Woods curls at his feet.

For starters, plant-wise, rare sits beside ordinary now, Tinker’s weed, raspberry bushes, elm-leaved golden rod, Pennsylvania sedge, dog violet, northern cranesbill. There’s a lush array of color, and sunlight where darkness ruled. But when Steffen started the restoration in 1989, more than a century of invasive buckthorn and garlic mustard had grown into a thicket so impenetrable here that he couldn’t see the base of some trees. Other spots were only reachable on your hands and knees. “The area was so dense there wasn’t enough sunlight for some plants to survive,” Steffen said, “and leaf litter (from the invasive plants) was so high in nitrogen it stimulated the earthworm population, which consumed root hairs of other plants and changed the pH of the soil. Basically, plants couldn’t survive, soil was essentially bare — seemed pretty hopeless.”

And McDonald Woods is healthier now?

“Yeah,” Steffen said plainly.

He wears a white mustache, a disintegrating ballcap and maintains long silences. He does not sell or even make any note at all of his achievements; he never even mentions them. Still, he’s been the “driving force” behind the health of these woods for three decades, said Gregory Mueller, the chief scientist at the Botanic Garden. “Wooded areas in suburban-urban areas are no longer independently self-supporting. There are too many stresses, they need to be managed (to stay healthy). Jim is getting this one as self-sufficient as possible, to bring back as many of the benefits as the woods brings. He’s a mix of curiosity and practicality, with an ability to just do it — we joke he’s ‘the machine.’ ”

Ask Steffen what these woods were like, before invasive species, he says, “I don’t exactly know.” He drives his golf cart across the Botanic Garden grounds in silence.

Then he unloads: “There isn’t a lot of historical information on the conditions. There was a guy who traveled on horseback through here and wrote down observations, so a lot of what we have is anecdotal. It was logged and grazed. It was Turnbull Woods originally, the Turnbull family lived on the other side of Green Bay Road. They were the original settlers, in the 1830s. They grazed cattle and harvested hay out of Skokie Marsh, which is now the Botanic Garden. They were dairy farmers. Cattle ate the plants, so it never got too dense here. But when invasive species showed up and filled in the gaps, it got dark. It became McDonald Woods in the 1990s, renamed after (the late) Mary Mix McDonald, who sat on the county board and helped us get the rights to the 100 acres.”

We rode on.

“I was hired originally to develop a specific 11 acres of garden that they didn’t really know what to do with, but I said it didn’t make sense to manage that 11 acres when they had all this woodland behind it full of invasive species.” So, for decades, he surveyed trees in McDonald Woods, studied fungai, counted spiders and small mammals. He erected fencing to slow a deer population that was strip-mining its plants (“but give most animals time and they figure you out”). He pulled clumps of invasive grasses out of the earth with his hands, and for a few years, he oversaw the removal of nearly 1,000 ash trees that had been infested with the invasive emerald ash borer insect, climbing into and (to avoid the infected trees from crushing healthy trees) detaching many tree tops himself.

The point is, he says, gesturing at the forest, is it’s all connected. “Restoring it doesn’t mean just restoring plants but all the individual things that live here. Lose one native plant and you might lose three other things that depended on that plant — like insects.”

We arrive at a forest shelter, open to the woods and constructed around an old stone fireplace, built by the Civil Conservation Corps decades ago, as part of the New Deal.

“Oh,” Steffen says.

A small 10-point buck watches, almost an arm’s-length away. Steffen stares back a moment, then the deer abruptly leaps off and Steffen returns to his office and his moths.

The next morning is cold. Steffen navigates his golf cart along Lake Cook Road, the sky dark at 6 a.m. The only sound is a buzz of insects murmuring at various pitches and volumes, like different models of cars revving in the distance. He steers the cart up a grassy incline then quickly and efficiently collects the traps, each of the devices obvious before dawn: Scattered throughout the forest is the soft purple glow from their UV lights.

He bends alongside one.

“It was a good night,” he says.

He straps the traps to the flatbed of the cart and drives back to a small parking lot behind the Botanic Garden’s science offices. There, he disappears inside then comes out with something unexpected: A large white cube, essentially a wooden frame with mosquito netting stretched across and sewn in place. He climbs inside the cube, sits on a footstool at its center, then grabs the first of four traps and opens the plexiglass lid. At the bottom of the basin are egg cartons covered in what looks like stray pencil marks — hundreds, actually.

These are small moths, but also beetles, spiders, wasps — whatever wanders in. Some moths flutter upward to the net, some crawl along the cartons; Steffen sorts slowly, placing moths he doesn’t recognize in tubes, releasing moths he’s familiar with, about 99% of his catches. He works in silence, stopping to note a new species or unusual find. “Underwing,” he says, raising the camouflage dress of a moth and revealing orange knickers.

There are 1,850 known species of moths in Illinois, so identifying 600 species within a modest 100 acres is “a wonderful effort,” said Terry Harrison, a retired entomologist from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign known for his own deep local dives into the insect. He said the study of moths in the Upper Midwest remains “a blank slate.” There are amateur insect collectors known for taking vacations, often in the Southwest, where they set up powerful mercury vapor lamps and draw in every moth within a quarter mile. But they often hunt the spectacular and colorful. “In a region where there is minimum study of moths,” said Mueller of the Botanic Garden, “Jim has painted our whole picture, of micro moths and everything else, with a remarkable rigor.”

Steffen lives near Zion, on the Wisconsin line.

He grew up in Manitowoc, banding birds for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at 15; he studied biology and environmental sciences at University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, he spent years creating cross-country ski trails for the state. His knowledge is broad — spiders, birds, invasive plants, restoration — but he’s no moth expert, he says. And when he retires (“shortly”) he’ll donate his specimens to the Field Museum (“if they want ‘em,” he says).

Driving in his golf cart in early morning, he mentions “the goal of all this” was never to return a single patch of Glencoe back to the 1800s. That’s never going to happen. “It’s not the same world anymore.” The goal was to improve the health and increase the biodiversity of native species in McDonald Woods. “But I wonder sometimes, with some moths, I wonder if I am looking at the last of a species, right in my hand.”

Chicago Botanic Garden ecologist Jim Steffen collects his moth traps in the early morning. (E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune) We sit in silence, the sky lightens.

“It’s so depressing, I hear. But it’s better than it was. It’s the best I could do.”

This story was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on Sept. 20, 2019.

-

Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Emily Nussbaum can’t keep up with all the TV and she’s OK with that

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago Tribune“Do you really want to watch TV with me?” Emily Nussbaum scrunched her face, gauging my reaction. She smiled tightly, then plowed forward: “I mean, I get it. But it just seems weird. It’s one of the things we could do. We could watch TV. I do have to watch ‘Chernobyl,’ so we could watch ‘Chernobyl.’ Or I could just describe to you how I watch TV? A lot of the time I’m watching a computer.”

We were in her living room, in the South Slope section of Brooklyn.

Her set-up was modest.

A TiVo machine connected to a flat-screen TV, 46-inches wide, just wide enough to avoid blocking the street-level windows it was positioned between. A dusty XBox, a dusty PlayStation — each at least a generation old. A lava lamp. Across from the flat screen, a couch, and curled on that couch, Bella, her chihuahua-dachshund mix.

So nothing fancy, and itself an answer to her question — why would anyone want to watch TV with Emily Nussbaum? She is the TV writer at the New Yorker, a 2016 Pulitzer winner for criticism, author of her first collection, “I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Though the TV Revolution” (out June 25). But more importantly, Nussbaum, as a critic, feels familiar, as uncertain and exhausted and angered and obsessed by TV as the rest of us. She has become a must-read critic at a time when the role of culture critics at media institutions is in doubt, tied in perception (if not practice) to top-down yays and nays, airless word-of-God judgments that look increasingly antiquated in a social-media age.

That’s not to suggest a Emily Nussbaum review is ambiguous — there’s nothing wishy-washy about referring to “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” as a cloying, grating “bright-pink escape hatch” from the gender politics and everyday combativeness of the Trump Era.

That’s not to suggest TV writing was a wasteland before her.

Only that few critics make as strong an argument for the importance of ambivalence, or simply that ambition looks differently on television: She rejects the idea that TV needs literary gravitas or cinematic scale. She makes a case for TV as TV, and not as an inherently “weak sibling to superior mediums.” Fewer critics still are as clued into how the audience’s real-time digital relationship with the mechanics and the creators of television has transformed the way that television is made and how we are watching.

On the underwhelming response to “Game of Thrones” finale: “The real Iron Throne may be the sort of appointment TV that ‘Game of Thrones’ represented.”

On the post-#MeToo legacy of “Louie”: “My mind locks up whenever I think about the series.”

On “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit”: “When I was pregnant my unsavory addiction felt something like pica, the disorder that causes people to eat dirt and fingernails.”

“A lot of TV critics even now seem to think their job is holding TV at arm’s length, to remind you of the baggage that TV has carried since it started,” said Mimi White, who has taught TV studies at Northwestern University since the early 1980s. “But Nussbaum is one reminder that a good reviewer is also sensitive to the ways that TV appeals.”

If an old cliche about television holds, that it’s a medium doubling as both family member and furniture, Nussbaum’s New Yorker reviews read as weekly therapy, about the ways this family is joined at the hip. TiVo, for instance. At her home, self-conscious about using the 20-year old DVR service, she said: “Remember when people first got TiVo and it had algorithms to suggest new shows? I liked ‘Buffy,’ so I got kung fu shows. One day I got (the 1948 musical) ‘Easter Parade.’ I loved it! Remember ‘G String Divas’ on HBO? People state their tastes reflexively now, but TiVo used to decide who you were. I didn’t want TiVO knowing I watched ‘G String Divas.’ What would it think of me?”

Like many writers, Nussbaum in person is an extension of her work, casually noting her likes (Tina Fey, reality TV), her dislikes (product integration, Jimmy Fallon), funny and caustic and rambling, with the brisk conversational manner of a Twitter feed, only generous. She meets you with a smiling rush of words, and as the chat goes on, she does not slow. Daniel Zalewski, a features editor at the New Yorker and college friend of Nussbaum, said: “The best thing in the world is Emily Nussbaum trying to explain why you’re wrong and a show is great. Like ‘Oh my gosh, no! Here’s the thing!’ Then there’s a rapid-fire, seductive argument — but one that’s perceptive about your own thoughts.”

When I ask her if she watches “Saturday Night Live,” a cascade of thoughts on late-night TV follow: “Some people get irritated by Samantha Bee and Seth Meyers and what they see as flaunting wokeness, but you know, at least they’re trying to engage. Seth Meyers is smart, that (segment) ‘Jokes Seth Can’t Tell’ is clever, people are put off by things that seem corny or self-congratulatory, which I get but there is good stuff. And look, I was disgusted when Jimmy Fallon ruffled Trump’s hair, which was gross to me, but OK, my point is that this is hard political stuff to pull off and maybe it’s not the job of ‘Saturday Night Live,’ but then I don’t have anything to say about ‘Saturday Night Live’ and don’t want to just offer my take.‘ Though maybe I should be doing that, I don’t know.”

We met at the neighborhood bar where she tends to write, seated in a dark-wooden booth so carved with graffiti that nothing is quite legible anymore. Then we walked to her house, where she lives with her two sons and husband, tech writer Clive Thompson. “He wants to watch TV with me, so maybe, I think, ‘Chernobyl,’” she said, introducing me.

“It’s such a sunny day out,” Thompson said. “Definitely watch a catastrophe.”

She cued up the Kanye West episode of David Letterman’s Netflix show “My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman.” The dog slumped against her. She lifted her laptop and took notes, then closed the lid, then opened it a moment later and continued. She watched in silence with a faint expectant smile, then said, “OK, how is it Letterman now comes off weirder than Kanye West?”

My thought exactly.

Depending how old you are, you might be surprised to learn being a TV critic wasn’t always the most obvious path to prestige in journalism. Nussbaum says she gets asked if she always wanted to be a TV critic. “And I think, ‘Why would I ever always want to be a TV critic?’ How in 1988 could this have seemed like a good idea?” TV, she explained, started “as this experimental, wacky form” that took chances on prime-time opera, on live teleplays. “But once TVs got cheaper and advertising took over, it’s not generally regarded as an art form, it’s addictive junk and bad for you. … So for years TV suffered from a hangover because of those origins.” Guilt by association was common.

You could write seriously about theater, books. But whenever TV was smart and thoughtful, the achievement was always couched, as good as a film, as smart as a novel. There’s a legacy of TV critics with clout, including Tom Shales at the Washington Post and Mary McNamara at the Los Angeles Times, but for much of TV’s history, the job somewhat mirrored the B-list role of the medium it covered. Alan Sepinwall got his start as a TV critic in the mid-1990s after writing online recaps of “NYPD Blue”; today he reviews at Rolling Stone. “But when I started, there was no equivalent to Pauline Kael, Roger Ebert. There weren’t those same models to emulate.”

Nussbaum, 53, said she wanted to be a writer, of some sort.

She grew up in Scarsdale, N.Y.; her father, Bernard, was a former White House counsel to Bill Clinton. She didn’t read a lot of criticism, she thought of her influences as Letterman, Steve Martin, Nora Ephron, poet Sharon Olds, cartoonist Lynda Barry. She studied English at Oberlin College, then spent time “as a drifty, crunchy person,” running the children’s program at a domestic-abuse shelter in Rhode Island, working as a real-estate secretary in Atlanta, trying to write a novel. She attended graduate school (New York University) for poetry, planning to get a Ph.D. in Victorian studies, until a “fortuitous” kidney infection put her in the hospital. She had been freelancing for magazines and newspapers, and decided she preferred, as she says, “the pleasurable dilettanteness” of journalism.

But during graduate school she had been watching and evangelizing to friends about the WB’s “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” She regards the moment now as her “conversion.”

“My odd super-villain origin story of sorts,” she said, “is that I would get frustrated how people would talk, understandably, about the brilliance of ‘The Sopranos,’ but discuss it as more than TV. Whereas ‘Buffy’ was condescended to. It was this beautiful and ambitious feminist myth about sex and mortality — it was trying to do large things, too. The difference was ‘Buffy’ was recognizably TV, the look, structure, the way it was broken by ads, even the title. But when I told someone to watch ‘Buffy,’ it led to arguments. I’m not in that same feverish state for it now, but it made me want to write about TV.”

Even as she studying Victorian literature and freelancing, she was posting anonymously on the early, influential TV forum Television Without Pity, known for its snark and obsessive recapping and conversations that went on for months. She says that if the site wasn’t “quite culture criticism as people knew it, it was a distinctive criticism for a more contemporary era, with a total flattening of hierarchy.” Journalists, fans, artists, TV execs — they were all posting on the site. Two regulars (whom we know about) included playwright Itamar Moses (“The Band’s Visit”) and TV producer Stephen Falk (“You’re the Worst”).

Sarah D. Bunting, one of the co-founders of Television Without Pity, said the site began modestly, out of frustration with the WB series “Dawson’s Creek.” “Which was trying to be ‘My So-Called Life’ and it was sucking at it. … I don’t think we were trying to be mean to anyone but nobody expected better of TV, and better was clearly possible, so why weren’t these people interested in doing better by TV? That was the motivation.”

The follow-through — episode recaps running a few thousand words, a communal dialogue as opposed to the hard-fast judgment of typical criticism — more closely resembled how people engaged with television, as knowing, dyspeptic coconspirators.

Several years after Nussbaum first posted on the site, even after she was hired by New York magazine to edit its culture section, she still hesitated at becoming a traditional top-down critic. Then she decided, “I should feel comfortable saying critical things about television because people are condescending to it. In a way, a negative review of television is a way of praising the medium — of saying it was worthy of serious criticism.”

At New York, she also created the magazine’s most popular feature, the Approval Matrix, a weekly grid bordered by Highbrow, Lowbrow, Brilliant and Despicable, onto which new slices of culture — poetry, film, opera, reality TV, snack foods — is given a coordinate. (It briefly became a TV series on Sundance TV; Nussbaum was not a fan.)

“I guess I have an issue with hierarchies,” she said, “though it’s not as simple as high-low. It’s way more about questioning how (the arts) are set against each other and encouraging something mushier. I mean, my book exists because after I started at the New Yorker, I ran into someone in the hallway and asked what she was watching and she said, ‘Oh, stupid guilty pleasures like “Jane the Virgin.”‘ I unloaded a maniacal speech on her about how it was one of the most thoughtful shows on TV! How it’s a show about storytelling! So she slowly walked backwards and I never saw her again.”

Her new book — largely drawn from her eight years as TV critic at the New Yorker — reads at times like a manifesto, for a new way of talking about television as an art form.

Time, for instance, is a more common subject for Nussbaum than, say, acting. “Because TV is not like a movie, TV doesn’t come out and that’s the thing. TV keeps changing, responding. And the audience is responding. I have nothing but sympathy for TV creators whose shows are huge then they have incredible pressure to come up with an ending. There needs to be language to acknowledge TV happens over time.” The person who creates a TV series, she added, is never the same seven seasons later.

“That’s the nature of TV,” she said, “it happens over time.”

Listening to her, it’s hard not to think of Pauline Kael, the New Yorker’s influential film critic, whose writing about movies altered how a generation of moviegoers regarded the medium. Indeed, Nussbaum is often compared with Kael, but she rejects the notion: “It’s a compliment, I know. It’s because we’re both women, both at the New Yorker. We both celebrate culture sometimes seen as junk. But so do others. Also, I didn’t grow up reading Kael.” Besides, added Sepinwall, “Emily may have a Pulitzer but Emily is also not as famous as Kael was, and that’s because it’s hard for any critic to generate that influence now. Nobody doing this job anymore has the power to get a large audience to ask, ‘I wonder what a critic thinks about this.’ That world is gone.”

Before we finished watching TV, Nussbaum asked me what she should watch next. She asks people this all the time. She calls up an app on her laptop that holds a long list of TV shows recommended to her by friends and strangers.

“‘Arrow?’” I offered, randomly.

“I heard that’s good,” she said. “I need to get to that.”

She won’t.

Or rather, judging by the length the list, I doubt it.

The list touches on streaming services, broadcast TV, web productions, old, new. Like you, she feels no need to catch up. Not anymore. No sane person would.

“When I started (at the New Yorker), I had this idea to alternate, network show, cable show, big show, little gem. That’s out the window. I would like to watch more, it’s enriching. But you know what also enriches? Living your life. I used to have a masochistic thing where if I pan a show I had to watch the whole season. ‘It might change!’ Now I don’t do that. I drop shows. I get irritated if a show is bad when there is so much to watch, but I feel self-conscious. I don’t want to hold it against creators of this stuff that I have a job where I get impatient. (For example,) ‘Maniac’ on Netflix. Emma Stone was good, it was cool visually. But pretentious, and in the aftermath, I worried I disliked it more because I was annoyed that I decided to watch it —you know?”

Who doesn’t?

“You don’t want to hold the immensity of choices against anyone. That said, it was a bad show.”

This story was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on June 17, 2019.

-

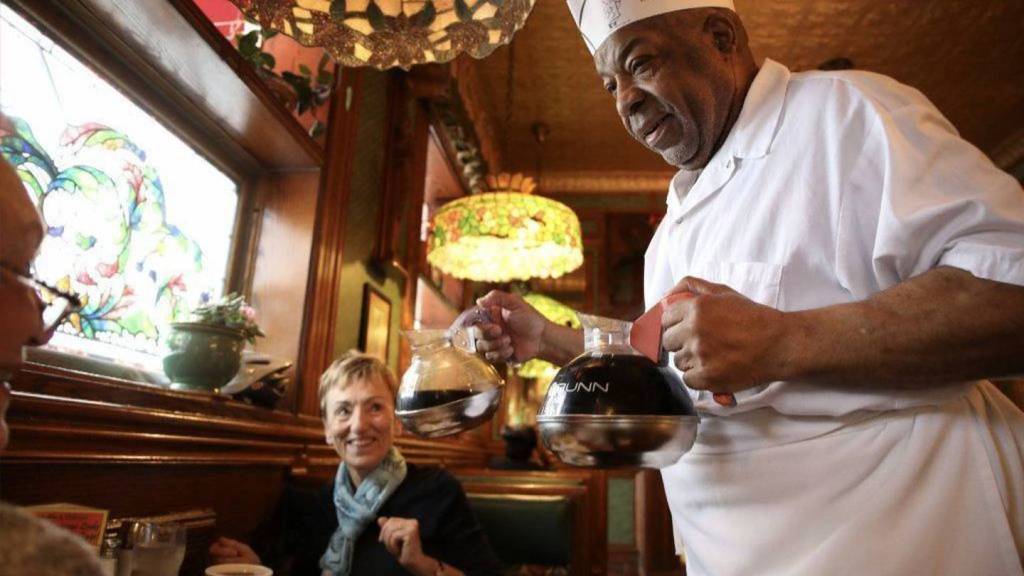

Meet the table busser who’s worked at the same Wilmette pancake house for 54 years

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneOthea Loggan came to Chicago and got a job bussing tables and washing dishes at Walker Bros. Original Pancake House in Wilmette. One of his brothers-in-law was the chef. Loggan lived on the South Side but he didn’t mind the long, early morning commute to the North Shore, clear across downtown Chicago and Cook County. He was just happy to be free of Mississippi, where he had grown up poor, one of 10 kids. Walker Bros. was relatively new then, and a fast success, establishing itself in less than four years as a breakfast staple for businessmen from Glencoe and hungover graduate students from Northwestern alike. Loggan himself had been in Chicago only two weeks.

He started March 30, 1964.

The Outer Limits” was on TV that night. The No. 1 song was “She Loves You.” The battle of the Gulf of Tonkin, which cemented the United States in Vietnam, was six months away. And two weeks earlier, Lyndon Johnson, new to the Oval Office, proposed to Congress the first War on Poverty.

Loggan’s starting salary was $1.15 an hour, the federal minimum wage, but enough, he recalls now, to save up and buy a small house, if you got lucky. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, roughly 40 percent of Americans in the early 1960s stayed in a job for 10 years or longer. Loggan never really intended to stay that long. He was only 18.

He didn’t really have plans.

On a muggy July morning, Othea Loggan walked into the kitchen at Walker Bros. Original Pancake House. He arrived as he had for decades, through a side door, at 5:50 a.m., a headlong wave of motion among a staff still getting adjusted to the hour. The president was Donald Trump, the No. 1 song in the country was “Nice For What” by Drake, and according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average job tenure in the United States was just four years. Or, if you worked in a restaurant, it was closer to two.

Loggan, however, was still a busboy.

He was 72 now. He had never left, never graduated to serving tables, never became a manager or a chef — he says he never asked to do anything else. So, he had stayed a busboy, for 54 years. The title had evolved since 1964; he was now a “busser.” But he still wore the kind of throwback paper hat that a busser wore in 1964. He made whipped butter, and squeezed the oranges for OJ, but mostly, he still bussed plates and glasses, tidied up the same dark wooden booths, passed the same windows inlaid with the same stained-glass foliage, noted the same line of customers snaking out of the front doors, received waves and hugs (and sometimes Bulls tickets) from the same regulars. He had seen generations of customers and co-workers pass through; he’d been there so long he watched Bill Murray go from neighborhood kid to superstar to venerated elder. When he squinted, the same teenagers were still curled into the same booths, the same infants tossed crayons under the same tables, the same captains of industry put away the same post-workout pancake stacks.

His 2018 commute wasn’t even that different than his 1964 commute. He lives in West Gresham, not far from 89th Street. He takes two trains and a bus in the morning, then back in the afternoon, four days a week. He rides the Red Line almost perfectly from one end to the other. Door to door, that means a roughly two-hour commute, each way.

Naturally then, for at least a decade, he’s fielded the same questions, all the time. Like, Why? Who busses tables that long? Why not find a job closer to home? Or retire?

Eventually people stop asking.

Because the more you talk to Othea Loggan, and the more you think about clearing plates of pancakes for half of a century, the more details seem both too obvious and too complicated — there are few satisfying explanations. There is only a man whose choices (amid a systemic lack of choices) offer snapshots, of the changing nature of work, of the lack of opportunities for people of color, of the assumptions we make about ambition.

“He could retire now,” said Javon Chambers, his grandson, himself a Walker Bros. busser for 15 years. “He’s financially straight and everything. I just think he knows when people retire, they die. That’s what he’s said: Old people don’t have nothing to do, they see their friends retire, and then they retire, and that’s when they die of boredom too. It’s like people who are married a long time — if one dies, the next goes right after. That’s like my grandfather and this place. He doesn’t want the will inside him to dry up.”

Other than holding the same foot-in-the-door job an unusual number of years, Loggan has not led an unusual life. Those who’ve worked alongside him for decades can’t tell you much about him. There’s no mystery, coworkers say, only a guy who doesn’t like to talk about himself; general manager Tom Zehnder said fresh details arrive at a trickle, years apart. Ray Walker, who has owned the Walker Bros. chain in the Chicago area since 1974, calls Loggan a friend and a “great man” — he sang Loggan’s praises for an hour — but he has never met Loggan’s wife, Claudia, and couldn’t tell you much beyond the basics. He’s not alone. When I called Loggan by his first name —pronounced “O-tha” — his coworkers often paused to recognize it. They only knew him as “Loggan.”

Othea Loggan speaks with customers at Walker Bros. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune) Always there, never late, good at his job.

The bedrock in a place defined by its permanency.

Loggan himself chafes at a lot of this. Of course he does. You would too. He’s rankled at the idea anyone could do any job automatically for so long without a complaint or regret. He says: “Back in the day, my son was young, I didn’t want to work weekends, I wanted to spend time with him. But I had to work. Now I don’t work weekends, and he’s older.”

He lets that settle in.

He sits huddled in a booth, silent, then blurts: “Why do you want to ask about my working here? I come to work, who cares?” He says it gravely, and I recall he said the same thing eight years ago, when I first asked him about his job; he looked at me then with a guarded wariness, rolled his eyes and walked away. The next time I asked him, he said OK but he wanted to get paid, Michael Jordan didn’t do commercials for free, and only Walker Bros. would see any financial benefit here, so why should he talk? Which is right. Whenever I saw him after that, he softened, or recognized the oddness in his job. But he was never eager to share. If he smiled it was like you won something. (Keeping with Tribune policy, money was never promised or exchanged for his participation in this story.)

He has a long face and heavy, unassuming eyes that, at the restaurant, scan the room even as he talks to you — he doesn’t like being unaware of what is happening.

As he spoke, words came in a fragmented, tumbling rush, as if he needed to say everything now so he could get back to work. He grew up in Greenville, in the Mississippi Delta. It was known for cotton plantations, tugboat manufacturing, and as a pocket of relative tolerance and diversity in the heart of the Jim Crow South; the Stein Mart department store chain was founded there by a family of Russian Jews.

It was also known for profound poverty and illiteracy, both ingrained and enforced. “I saw stuff there that made you feel like you had gone back in time,” Loggan says. “There was no money.” (Indeed, the month he started at Walker Bros., a U.S. District Court in Mississippi upheld the use of literacy tests as a measure of who could vote in the two-thirds African-American community; and as recently as a decade ago, according to literacy surveys, as many as 25 percent of Greenville adults were considered illiterate.)

Loggan said he never really knew his father, but his mother, who died in 2000, was the chef in a Greenville soul food restaurant for 40 years. “She would cook breakfast, lunch, then have food ready for staff on their breaks — she was dependable, and she liked her job, and she would tell me that I would have to get along with people — I’m a lot like my mother.” But with four brothers and five sisters at home, “she could only help so much, and I stopped my learning early and came to Chicago.” He moved with a sister, at the end of the Great Migration that brought millions of black Americans out of the South.

While he talks, he works his hands together.

He says softly to himself, “Cramps.”

Asked why, after so many years, he never asked management for a less demanding job, why he stayed at the same pancake house so long, Loggan doesn’t register the question, as if those questions hadn’t been there in a long time. Ray Walker said he’s asked Loggan about advancing but “Loggan doesn’t want anything else — he’s said he’s fine where he is.” He said, “I think he views this as a place where he knows people, he’s safe and comfortable.” He said Loggan “was the complete opposite of a Black Panther kind of guy,” never an advocate or rabble rouser. He said that limited schooling “probably helped smooth out his world — I would doubt Loggan really ever dreamed about buying a Cadillac.”

Loggan himself, asked those questions again and again — Did you ever want to do something else? Did you ever want to advance? — only answers:

“It’s as simple as this — people treat you well, you don’t mind coming to work. Ray is a good man. Maybe I wanted to do something else? I don’t remember. This is not an easy place to run. People come in late, don’t come in at all, you have to hire — sounds like a headache, man. Who wants to wake up with that responsibility? I’m dependable and they don’t worry about me, but I’m not a manager.”

Jose Antonio Chambers, Loggan’s son, a Chicago police officer, told me, “My father is old school — never complains about nothing, never. My mother too. There were times it was hard to get food on the table, and they did not complain.” He said his father was great with numbers, that “if he hadn’t grown up in the South at that time, if opportunities had been there, he might have done something else. But he got this job, he did it well, held on to it, and there needs to be a lot of respect for someone like that.”

His father entered the workforce at a time when, if you were dependable and didn’t rock the boat, you might assume rightly that you could remain in a job for most of your life. If you were white.

Logan will retire — maybe, someday — at a time when transient employment is the norm, when no one assumes an employer will show loyalty to them (and vice versa).

Ambition, in a time of low expectations, in a country defined by inequality, can mean holding on to what you have, internalizing your place in the world. “I think Loggan wanted to fit in somewhere,” said chef Pat Levy, also known as “Popeye”; he has worked at the restaurant 42 years, arriving in Chicago from Jamaica. “I think Loggan just decided to be a busboy. He is content. It’s all he wants. So I ask — isn’t that OK?”

It’s hard not to notice the social gulf between customers and staff in a place like Walker Bros. Not that any of this is unique, of course. The optics are just a bit more evident: The staff is black and Latino, wearing old timey diner hats, serving comfort food to mostly white, affluent, well-educated North Shore families, the dining rooms wrapped in polished wood and stained glass more common a half century ago. That said, it’s also not uncommon to see customers giving bear hugs to beloved bussers and servers. It’s a warm community hub, a fixture of the local culture. “But the customers help us a lot, tip-wise,” said Derrick Rumbult, known as “Breezy,” another Jamaican native, who has bussed tables here a mere 38 years.

Othea Loggan, a busser at Walker Bros. Original Pancake House where he has worked for 54 years, resets a table. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune) Loggan, after 54 years, along with his fellow bussers, makes a little more than minimum wage — $2.75 more. (Management says this averages out to roughly $14 an hour with tips, before taxes. It also notes he gets five weeks paid vacation and annual bonuses.) What he doesn’t receive: a pension, health care, a typical 401K plan.

Again, none of this is unique to restaurants.

It’s just a little more pronounced here.

Winston Brown, another busser (for the past 38 years), taps his chest and a red light glows through his white coat — “I’m on dialysis,” he says. “Medicare only. We make just enough to pay bills — sometimes. When I started here, there was one Walker Bros., this place, and now there are seven of them. And what do we get? We get to pay our rents.”

Any savings?

He laughs sardonically.

Loggan doesn’t complain.

Rumbult, similarly, says management “does a lot, but we could always use help.” In a sense, their major benefit is a feeling of job security. With new hires today increasingly less likely to stay at a pancake house long, Ray Walker says his loyalty to his aging bussing staff has only deepened. His father, Victor, who started Walker Bros. with his uncle Everett in 1960 (franchising the business from an Oregon pancake house chain), hired Loggan. He says he probably treats Loggan a little better than the rest of the staff, but hesitated to go into detail: “Others would want to know what they’re not getting.” For instance, the company took out life insurance on Loggan (payable to his wife); Ray says that for years he’s set aside about $50 a month for Loggan, as an informal retirement fund (subject to a 30 percent penalty for early withdrawal). Yet retirement sounds iffy.

Bussers and servers at Walker Bros. stay so long, involuntary separation often means they got sick or died.

I asked Ray if it was true he brings Loggan his old clothes.

He said, yes, occasionally: “A lot of the guys, you see them in the same pants every day, or in clothes in need of repair — many of them don’t have a lot of clothes to wear.”

Well, then why not pay them more?

He said they get annual bonuses.

He said, “there are a lot of ways to reimburse people.”

At 5:07 a.m., on the mark, as Loggan promised, a Red Line train pulled into Howard. Cars were sparse, one or two passengers apiece. Loggan ambled out and waited. He wore a Cubs hat, a Cubs T-shirt. A Purple Line train arrived. Loggan took a seat and rubbed at his knees. He’d been awake two hours, likely more.

Othea Loggan at Walker Bros. Original Pancake House in Wilmette, circa late 1960s. (Othea Loggan photo) He wasn’t feeling good, he said. His aunt, in St. Louis, his mother’s sister, she died the day before. She was 98. He couldn’t shake it. He called his manager, told him he felt bad, his aunt had died, but he’d be at work. He massaged his hands. His grandson, Javon, who makes the commute with him, curled sideways into a seat, hoodie zipped up and pulled over his head, to catch an extra few minutes of sleep.

At the Davis Street station in Evanston, having long ago internalized exactly how much time he had before the 213 bus pulled up, he walked across to 7-11 and bought a sealed package of bologna slices and a single lottery ticket.

“Good morning,” he said to the clerk.

Crossing back to the bus stop, he said “Good morning” to his fellow riders, then quieter, more as a reminder, still thinking about his aunt, he mumbled, “We all got to go that way. And nothing you can do. Better to be with people.”

The routine is a comfort.

Of course, others have stayed in the same job as long or longer. There was a police officer in Milwaukee who stayed on the force 61 years. There was a cashier at a McDonald’s in Indiana who stayed a cashier 44 years. And that’s just near Chicago. But since the Great Recession, more Americans tell more surveys they can’t afford to retire. According to federal labor statistics, the fastest-growing workforce in America are 55-years old and older; not long ago, those people were our slowest-growing workforce.

Loggan is just an extreme example.

Ana Martenez, 54, a server at Walker Bros. for 16 years, said: “I look at Loggan and I think about those people who tell you they can’t get up in the morning. I mean, some of us do it all the time. Life is too expensive. But Loggan will have to stop. Everyone has to stop some time.” Loggan said he thinks about this daily. He’s not ready. Retirement would mean watching baseball, running errands with his wife, who still works herself, as security at a South Side school. He has a son and a stepdaughter, but they’re both adults.

He got on the bus.

For years, before there was a bus, he would walk to work from the train station, up Green Bay Road at 5 a.m., in the rain and the snow. Many times he would be stopped and questioned by police. In fact it happened so often Bruce Smaha, a former Wilmette officer (and close friend of Ray Walker), began giving Loggan a ride to work in his squad car. Smaha said he did it until he was reported himself (by a concerned citizen) and reprimanded by superiors. These days, the commute is long but smooth; Loggan gets dropped off across the street from the restaurant.

The pink neon of the Walker Bros. sign glows faint in the rising sun. “Popeye,” Loggan says, passing the chef, who stands on the sidewalk, smoking and thinking before the doors open and service begins. Loggan enters through the side and before taking off his coat, he begins arranging metal pans. Then he churns butter, squeezes oranges. “I need to sleep better,” he says without looking up. “But you know, some people you just can’t stop thinking about.”

This story was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on Sept. 6, 2018.

-

How about rethinking a cultural icon? The front lawn.

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneOctober is here, and it’s a good time to let your lawn go to hell.

You could do this literally, via Halloween skeletons and a few well-placed ghouls. Or figuratively, via inattentiveness and noncompliance with civic ordinances, letting autumn take its course, browning away emerald until you’re left with straw. Should you choose the latter, understand: You are not alone in feeling a big fat shrug. The American front lawn, the postage stamp of grass spread before a set-back house, the stage upon which you display status, the frame inside which you project taste, that one-time signifier of leisure that came to suck up leisure time, is increasingly seen as a waste. When it’s seen at all: It’s hard to spot a front lawn in pop culture these days. Meanwhile, in the real world, home developers, real estate agents and landscapers say you want less lawn.

Sometimes, no lawn.

“I don’t know if it’s a majority of homebuyers,” said Allen Drewes, president of the Home Builders Association of Illinois, “but people don’t have time to devote to lawns — or local codes for maintaining lawns. I swear, if people could have plastic shrubs they would.”

According to NASA, there are 40 million acres of turf grass in the United States — lawn, in a sense, is our largest crop. Individually we spend, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 70 hours a year mowing our lawns; and as a nation, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, we pour 9 billion gallons of water daily on those lawns. Nevertheless, in the past two decades, according to the U.S. census, the average new home has grown 21 percent, even as the average parcel of land it sits on has shrunk 400 square feet. And now, as millennials leave cities for suburbs, “They just don’t want the commitment that comes with lawns,” said Chicago real estate broker Erin Ward. “They’re happy with a tiny patch — they don’t equate their front lawn with status.”

So, a modest proposal:

Since we’re already questioning the foundations of our nation, toppling monuments to institutions that no longer work for many, how about rethinking another cultural icon?

The front lawn.

After all, your front lawn is not an inevitability. It’s a work of art — an antiquated design aesthetic, a handed-down invention, one we stopped noticing ages ago yet remain coerced by property codes to maintain. There was a time when the front lawn was tied largely to contentment, to everyday middle-class life: Anyone who grew up in a suburb has a mental slide show of images — bikes cast to the side, lazy games of catch, parents admiring their green thumb, trick-or-treaters, snowmen and nervous dates idling in curbside cars — linked inextricably with front lawns. In earlier eras, these were reflected through sitcoms, light family comedies, late-century Updike novels. When we had free-range children, a kid’s weekend would begin a lot like that image of John Wayne in “The Searchers,” hovering at the front door, an expanse of land before them. Then, at least since the 1970s — John Carpenter’s “Halloween,” say — our image of American front lawns became less benign.

On the cover of “Little Fires Everywhere,” the new best-seller by novelist Celeste Ng, we see the Cleveland suburb of Shaker Heights, an overhead of front lawns and homes at dusk. Nothing is happening, and yet it’s hard not to look askance at a neighborhood so seemingly perfect, said Jaya Miceli, the book’s designer. “You know all can’t be right.”

The American front lawn, in short, outlived its original meaning.

As Tom Stoppard wrote in “Arcadia,” his 1993 play about time and gardening: “English landscape was invented by gardeners imitating foreign painters who were evoking classical authors. The whole thing was brought home in the luggage from the grand tour.” But in the centuries since that luggage arrived in U.S. suburbs, we came to take the front lawn for granted, said Ted Steinberg, a professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and author of “American Green,” a 2007 history. “If we’re only now on to what a boondoggle the lawn is, it’s because we’d forgotten that lawns are a multibillion dollar industry, and a story — with a beginning, a middle and, likely, an end.”

We forgot that front lawns once meant something deeper than Kentucky bluegrass.

Think, for instance, of that uncomfortable scene in “The Great Gatsby” where Jay Gatsby stands with his new neighbor, Nick Carraway, at their property line and, unable to resist, blurts out that Nick needs to mow his lawn. Nick narrates: “We both looked at the grass. There was a sharp line where my ragged lawn ended and the darker, well-kept expanse of his began. I suspected that he meant my grass.” By morning, disturbed by this hiccup in their pastoral landscape, Gatsby has chosen the nuclear option of suburban passive-aggression: He sends over his own groundskeeper to mow the grass.

Gatsby, a man with an infamous yearning to live above his status, understands that, however immoral he may be in other matters, the front lawn is a cultural agreement to take seriously. Nick may not be as successful as Gatsby, but keeping one’s front lawn in order, doing one’s part to maintain the unbroken green carpet you share with your community — it’s all part of the social contract. Fitzgerald’s lawn was a kind of a quiet reminder of the contradictions of the American Dream. We want to stand out — but fit in.

Which may be an American truism, but the front lawn is also a Chicago story. Never mind that, according to Bloomberg, the Chicago area has slightly more than 10 percent of the 100 wealthiest suburbs in the U.S. — including Winnetka (No. 10), Glencoe (No. 12) and Wilmette (No. 95), epicenter of the John Hughes-verse, which provided some of our most pervasive images of front lawns in pop culture. The Chicago area holds both the origin, and pushback, to the front lawn.

The classic suburban image of a stamp of grass and a home set 30 feet from the street: In the United States, this was pioneered in the western Chicago suburb of Riverside, one of the first planned communities in the nation. It sprung from a 1869 plan by landscape artists Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, the latter of whom imagined a river of grass, flowing house to house as if the residents lived in a park. They were influenced by landscape designer and writer Andrew Jackson Downing, who likened 19th century America to a disheveled toilet; he sought a nation where yards were “mown into a softness like velvet.” Olmsted’s vision for front lawns was partly a hedge, so to speak, against the questionable taste of Chicagoans. As he planned Riverside, he wrote: “We cannot judiciously attempt to control the form of the houses which men shall build. We can only take care that if they build very ugly and inappropriate houses, they shall not be allowed to force them disagreeably upon our attention as we pass along the road.”

Well, then.

If the front lawn initially played a communal, egalitarian role in America, like egalitarianism itself in this country, that role proved more idealized than actual. Suburbs became equated with a cultish conformity — or as Ernest Hemingway supposedly said of his hometown of Oak Park, the suburb was full of “wide lawns and narrow minds.”

“The yard, the suburbs, it comes to symbolize both American utopia and dystopia,” said Matthew Lassiter, a professor of history and urban planning at University of Michigan who teaches a history of suburbs. “It’s the cheapest critique, just the easiest way to go: ‘Behind this fence and front lawn, all is not what it seems!’ Your yard as this gateway to a lot of pathology — it’s an old trope, but impossible to separate from the image now.”

Your front lawn, in a sense, became a malignancy, a vacant space within a vacant place, soulless and mowed to a sterile sheen — cultural shorthand for the dullness covering a cancer. Think of all the front lawns in the new movie adaptation of “It” — long and wide and distracting from the threat gestating beneath the town’s idyllic streets, covered up by village elders. Ng’s “Little Fires Everywhere,” in which people allow bad feelings to simmer for way too long, begins with a house fire, its main characters standing on the front lawn: “Lexie watched the smoke billow from her bedroom window, the front one that looked over the lawn, and thought of everything inside that was gone.”

If these are cliches, they’re potent ones — tied closely, curiously, to 19th century landscaping intentions of using suburban lawns as vehicles to dictate taste and order.

When we do see a front lawn in a sunshiny light now, it’s often a bit of harmless nostalgia. “The Goldbergs,” the charming ABC comedy starring Chicago’s Jeff Garlin, is set squarely in the 1980s, and full of modest front lawns. One of the best moments in the latest Spider-Man movie, “Spider-Man: Homecoming,” is when Peter Parker darts through a series of upper-middle class yards — a cute homage to a similar scene with Matthew Broderick in Hughes’ “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” itself shot partly in the residential yards of Winnetka in the ’80s. Back then, the use of a front lawn was about appearing relatable — Molly Ringwald’s lawn in “Sixteen Candles” seemed just as ordinary as your own.

But generally, pop culture — often created by cultural tastemakers who left their suburbs for a metropolis and never returned — taught us nothing good happens on a front lawn.

People pass out on front lawns. Doors are slammed in faces and retreats are beaten across front lawns. In horror movies, peek behind your window blinds and unknown assailants stand silently on front lawns, hatchets in hand. In artier works of nostalgia — “Mad Men,” “Far From Heaven,” “The Virgin Suicides” — a front lawn is a portrait of lingering repression. More than one person interviewed for this story said they prefer the backyard and would never in a million years allow their children to play in the front yard — because who knows what’s lurking? That sounded a bit like those 2016 fears of clowns: Here lies a benign cultural icon, which simply does not feel so benign anymore.

In “Logan Lucky” and “Stranger Things,” lawns are untended, muddy — set decoration for income inequality. On “The Sopranos,” in “Ordinary People” (shot in Lake Forest), front lawns exude entitlement. On NBC’s “The Good Place,” a sitcom set in a utopian afterlife where all front yards are perfectly green, the Good Place is revealed at the end of last season (spoiler!) to be a literal hell. Lassiter, at UM in Ann Arbor, begins his class on the suburbs with a clip from perhaps the most memorable use of a front lawn in American film, the opening of David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet,” with its soft-focused reverie of suburbia, its white picket fence, its senior mowing his lawn — then collapsing of a heart attack as the camera glides below the turf, to find ants gnawing a severed ear.

Your front lawn is a lie.

In a 1989 New York Times Magazine essay about the lawn, journalist Michael Pollan, noting the zombielike cycle of refreshment granted by fertilizers and pesticides, wrote: “Lawns are nature purged of sex and death. No wonder Americans like them so much.”

To visit 2017 Riverside is to witness the rise and fall, and pros and cons, in real time, of Olmsted’s vision. Lawns flow house to house as intended, matching the rolling parks along the Des Plaines River. Yet driveways and walkways snap the mood. Few allow their yards to grow out of control; a local property ordinance dictates that grass should not grow taller than 8 inches. The social contract seems intact. But as in many suburbs, it can be hard to spot life. Drivers blast through winding streets, and a sign tells them to slow down, children live nearby — and yet where are they? They’re not out front.

Olmsted’s prototypical lawns, and the streets of Riverside, look not so much ideal now as sprung from movies and TV, for better and worse. Its modest front lawns wouldn’t look out of place on “The Simpsons”; its ornate Victorians — you can’t help wonder if the surreal corrosiveness of “Mother!” waits inside. Still, said Constance Guardi, chair of the Riverside Historical Commission: “Though we live in Olmsted’s design, I doubt anyone here is overly concerned with what his front lawns meant.”

Like the rest of us, even Riverside is removed from the lawn’s intention.

The front lawn began on British and French estates in the 18th century. Postcards of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and George Washington’s Mount Vernon, partly inspired from European lawns and gardens, circulated through the young United States. After the Civil War, as families moved to the borders of urban centers, Frank J. Scott, a popular writer of early landscape design books, argued for front lawns that — unlike European pastorals, ornamented with gardens and grazing cattle, and used for games — simply displayed one’s good fortune. It was a sign you could afford to own a patch of land that provided nothing but beauty itself. He wrote that it was “unchristian” to place, between the front of a lawn and a home, anything that distracted from one’s wealth.

“By the 1950s, it’s firmly rooted that a front lawn is a painting, a non-productive space,” said Elaine Lewinnek, a professor of American Studies at California State University, Fullerton, and author of 2014’s “Working Man’s Reward: Chicago’s Early Suburbs and the Roots of American Sprawl.” “The front lawn is designed to be useless, to simply increase property values. It’s also intended to separate neighborhoods that have lawns from cities — you see rules against drying laundry in front yards, for instance, because suburbanites are different than ‘those people’ drying clothes in public (in the city). ‘Sophisticated suburbanites use machines.’ Still, you need a great lawn to fit in. William Levitt (who created the seminal planned community of Levittown, N.Y.) said if you own a lawn you couldn’t be a communist — you had too much to do.”

A small anti-lawn movement began in the 1960s, sprung partly from this pressure to maintain appearances. Lorrie Otto, a housewife just north of Milwaukee, created a stir when she let her front yard revert to prairie. She found her lawn wasteful, boring — and many agreed, starting “Wild Ones” groups that, to this day, advocate for naturalistic landscaping. “This argument against lawns, it gains its steam in tandem with the ’60s environmental movement,” said Terry Ryan, a landscape architect with Jacobs/Ryan Associates, whose work includes Chicago Riverwalk. “People start to realize lawns take water and chemicals to maintain — sometimes herbicides and insecticides — and though grass is green and cooler than pavement, it starts to seem like a poor use of resources.”