-

Stupefyingly difficult U. of C. Scavenger Hunt marks 35 years with Olympic condoms, aerial pancake flipping and Rube Goldberg machines

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneThe 35th annual University of Chicago Scavenger Hunt — which is nominally a scavenger hunt but closer to a campus tradition wrapped inside a multigenerational class reunion bundled into an elaborate prank requiring the cooperation of hundreds of students, dozens of faculty, family, friends and government officials — concluded Sunday night. The winners were the students and alumni of the Snell-Hitchcock residential hall.

To win, they jumped through hoops. Many hoops. They located a list of scavenger hunt items from the first hunt in 1987. They found an official Olympic condom. They flipped a pancake 35 feet. They brought a mariachi band into a restaurant. They invented a beer glass that screams whenever it reaches room temperature. They constructed a Rube Goldberg machine that played music. They sewed a Magic Eye-style quilt depicting the walking trails of Millennium Park. They built a scale model of a 3200-series CTA train car with working doors, an LED sign for stops and automated announcements. They secured the written endorsement of California Sen. Dianne Feinstein.

They were far from alone. There were 24 teams and about 300 contestants. The list of stuff to find, do and/or construct was 243 items long.

They had four days.

According to tradition, the hunt begins with the release of the list on a Wednesday in May, then ends, sardonically, with the judging of contestants on Mother’s Day. If you stumbled across Scav, as it is known in Hyde Park, you would struggle to decide if it was a crafting fair, a science fair, a spirit rally or a Dadaist art revival. For a time, Guinness World Records claimed it as the world’s largest scavenger hunt.

“But I see it as an exercise in project management,” said Scav judge Cat Scharon.

“I think of it as Mardi Gras meets the Great Books meets Theater of the Absurd,” said John Boyer, college dean at the University of Chicago. “It’s a fascinating cultural transaction, but when students start to build nuclear reactors in their dorm rooms, it gives one pause.”

He’s only half-joking.

“Mostly we thought this would be fun,” said Diane Kelly, one of the founders of Scav, and now a research associate in neuroscience at the University of Massachusetts. The idea came from fellow student Chris Straus, now a professor of radiology at the school. In the 1980s, “we were just University of Chicago students, which means we spent a lot of time studying. This was before people were calling it the school ‘where fun goes to die.’ The student body was intense, so a weird event just before finals was welcome.”

But in keeping with the school’s pedigree as a home to Nobel Prize winners, the kind of place with the brainpower to build the world’s first nuclear reactor beneath what was then the bleachers of its football field, things got baroque pretty fast. That first year, the list of hunt items was relatively modest, including a zoo souvenir and a bus ticket to Iowa. By 1999, two contestants, using scrap metal, carbon sheeting and thorium powder scraped out of vacuum tubes, constructed a working nuclear reactor in their dorm. “When we put together these lists, we laugh a lot, because we don’t actually expect anyone to make some of this,” said Sabrina Sternberg, who was one of the judges. “And then they do.”

Just before the Scav judges released this year’s list of hunt items, just before midnight, dozens of students gathered in the courtyard outside Ida Noyes Hall on 59th Street. They were grouped into mobs, waving flags and signs, and taunting each other. Which evolved into: “Give us the list! Give us the list!”

That’s the first tradition of Scav.

After receiving the list, there is also a breakfast the following morning, a couple of parties, a formal dinner, a silly Olympics for additional points (hence the pancake toss), and new this year, the construction of a snowman on the quad (using only coleslaw). But the list and the hunt itself is the thing, and past lists have asked for: a CPR dummy, an Aztec death whistle, the longest churro, a Stradivarius violin, half a bowling ball, Toni Preckwinkle, proof that a University of Chicago diploma is as absorbing as a Brawny paper towel, a CT scan of a Furby, a gingerbread house of ill repute and one share of Green Bay Packers stock. For points, Scav contestants have eaten their own umbilical cords, gotten engaged, been circumcised, shot music videos, made wine in three days and undergone appendectomies. They have coordinated entire dorms into raising and lowering the window shades to replicate a game of Tetris on a building facade. They have gotten tattoos that read: “Sorry about the syphilis. Can we still be cousins?”

Some items on the list are puzzles, while some demand creative interpretation.

But then, so does just about everything else having to with Scav.

Even as students were outside chanting “Give us the list!” the judges were huddled in Ida Noyes Hall, drinking and goat wrestling, pressing shoulder against shoulder for dominance, chanting: “Two judges enter! One judge leaves! Two judges enter! One judge leaves!” They wore sailor caps, just because. One of them, Reed Mershon, broke away and walked to the courtyard and, as “Give us the list” hit a crescendo, he said: “I’ve been waiting three years for this.” The past couple of years, they had virtual Scavs, and while contestants said these worked surprisingly well, the camaraderie was missing. The judges, most of whom were recent alums, felt a responsibility to keep the tradition humming.

So just before midnight, the teams were invited into the main hall of the building. The judges gathered on a staircase and tried to explain a few rules, but the room grew loud, rowdy, chaotic. One student played an accordion, another was dressed as an armadillo.

At the stroke of midnight, the list was introduced and the teams scattered.

They had four days and counting.

But first, one more tradition.

Before being handed the list, contestants must complete a few challenges. The clock is ticking. In the past, lists have been suspended high above the floor and surrounded by “15 feet of lava,” requiring teams to improvise a solution. One year, lists were buried on the beach at Promontory Point. This year was more of a gentle welcome back. Drink from a baby bottle. Find the marked pea in the jar of black-eyed peas. Smash a plate. After each task, a few pages of the 18-page list of items and rules were released.

Typically, what happens then is the teams regroup in their dorms and sort out pages and translate the often cryptic descriptions (“a teammate with a heart of gold”). Some blow up the pages and wallpaper rooms. Some construct spreadsheets and databases. One of the reasons Snell-Hitchcock, which has won a disproportionate number of Scavs, is always the team to beat, said captain Daniel Vesecky, is because their dorm makes Scav a year-round priority, using about 50 dedicated students, then cycling in another 100 or so; they keep stockpiles of random materials they might need, and break the team into specialized groups dedicated to food, science, sewing, construction, etc.

As Wednesday night became Thursday morning, students waiting for their teammates to gather all the pages read through what they had, and there were gasps and laughs.

“I’m so confused,” said Sahana Jain, “they want … what?“

Another team moved through the hall in a kind of flock, led by Harper Schwab: “OK, first we have to make sense of all this. Item number 74, ‘a working toilet for rodents.’ Easy.”

They passed Max Moncada Cohen, who was saying to his friend Jonah Fleishhacker: “Oh, right here, I’m sure we can do this.” Item number 207: a cinnamon bun hairdo, “using a single, continuous roll of that delicious, gooey dough.” Doable.

And yet, the list itself was labeled: “The Zeroth Annual 2014 University of Chicago Scavenger Hunt List.” This was because some items required teams to arrive at a designated time and place, but the catch was that each of the times corresponded to a 365-day 2012 calendar divided into 15-minute “days,” distributed across roughly 84 hours of Scav. Thus, item number 2: “Meet us at the center quad on June 13th,” but bring your own custom fruit festival, with a cake, carnival games and pageant winner.

Convoluted? Exactly.

Writing the list is a five-month process that starts in January, which is one reason alums tend to play a large role — they have a bit more time than the students. They also use Scav as a mini-class reunion. Some fly in for the week. As with the Supreme Court, Scav judges serve for life. Indeed, Scav is so ingrained in Hyde Park culture now that the list has a five-page style guide. Teams of alumni have formed political action committees. Some seek out sponsorship from local businesses. One team is a nonprofit that wrote into its bylaws the promise that, should it ever win a Scav, it would immediately disband.

None of which, by design, makes much sense. This is exactly why, talking with students and judges, some of them wonder if Scav can survive for another generation.

“Scav’s lost its edge at least three times,” said judge Cass Cohen, dryly.

Students are forever declaring it not as edgy as it was. This year, the usual road trip portion of Scav — which had contestants traveling as far as Nevada for items — was scrapped for logistical reasons. More than one contestant told me they feared for the contest because of the kinds of students that the University of Chicago is attracting now, career-conscious types who seem less willing to waste four days on an esoteric goose chase. But Dean Boyer said every student body tends to worry that the new class is watering down the school’s reputation of eccentricity, “and I don’t see Scav normalizing.”

In fact, he said, the school sort of finds it charming and clever; past undergraduate applications have even incorporated questions from Scav lists into its essay portions.

Kelly said the creators of Scav didn’t expect the event to survive the internet. “Trivia questions themselves became trivial, and when you can obtain a whole lot in 24 hours from Amazon, it’s not a challenge. So stuff you can do and make became prominent. But that’s when we realized how invested people were.” This was 30 years ago. They asked for a soda can with a 5-cent deposit. Indiana, Michigan and Iowa had 10-cent deposits; Illinois had none. So a contestant went to Midway International Airport, boarded a standby flight to New York, bought a can of soda in the airport in New York, then flew back to Chicago.

One point.

Nobody gets every point.

There has never been a perfect Scav score; even the first list in 1987 asked for a dean, “nude, gagged and bound.” This year, no team was able to get a selfie with a shipwreck off Lake Michigan, though at least two teams climbed into dinghies and gave it the old college try. Still, incredibly, Tula Hanson and Audrey Leonard, captains of the Woodlawn East team, got item number 39: “an official statement from the University of Chicago stating unequivocally that ‘the University of Chicago is full of (expletives).’”

They got it from the admissions department, “which responded so fast,” said Hanson.

Woodlawn East, in its first year in competition, came in second place. They won nothing. No prize, no nothing. Unless you count an ashtray, made from a taxidermied deer hoof. Then again, first place received the same thing — nothing. Unless you count a ceramic fish. Really, they just got bragging rights.

Remember, you were young once, too.

This story was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on May 11, 2022.

-

Justin Green, a pioneer whose Highland Park childhood led to a new confessional kind of comic, dies at 76

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneJustin Green, a Chicago native whose early underground comix of the 1960s and 1970s influenced several generations of artists to adapt their most painful personal experiences into comics, died recently.

He was 76 and had been in hospice for five days. He had colon cancer, said artist and writer Carol Tyler, his wife of 38 years who announced his death via social media April 23.

He was “a great one for thinking differently about everything,” she said, though in the end, she added, he never had a colonoscopy and thought taking vitamins would be enough.

He was an enigma, even by the standards of a profession full of enigmas.

He was born in July, 1945, and grew up rich and painfully polite in Highland Park, though his signature comic was “Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary,” a transgressive work full of graphic sexual imagery and angst drawn from his childhood. On its first page, Green (as Binky Brown) is bound and dangling by his ankles from a dank basement wall, addressing the reader:

The Saga of Binky Brown is not intended solely for your entertainment, but also to purge myself of the compulsive neurosis which I have served since I officially left Catholicism on Halloween, 1958.

What follows was a sweaty, 43-page account of youthful guilt, self-mockery and all-consuming obsessiveness (he would suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder his entire life), so evocative he would receive a postcard from a fan named Kurt Vonnegut, who wrote: “It must have been hell for you to get it exactly right. Now I know what it’s like to have a Catholic upbringing.” When Green gathered the courage to call him, Vonnegut added: “I could see that the work came from a permanently damaged brain.”

Green would later described the act of writing “Binky Brown” as an “exorcism”; it was never lost on him that a famous cousin from Chicago, William Friedkin, directed “The Exorcist.” The book ends with Green sitting in his underwear surrounded by statues of the Virgin Mary, which he smashes, metaphorically freeing himself of organized religion.

A 1973 Tribune headline for an article on underground comix (already describing Green as a pioneer) reflected the mainstream reaction of the time: People’s fine art or porn?

Green had always thought that the book offered “truth too painful” for a large readership. Instead, “Binky Brown,” published in 1972, become a benchmark for cartoonists, pushing the limits of how much a comic could (or should) reveal about its creator. In the circular way influence and artistic creation often works, underground legend R. Crumb, whose work had influenced Green and “Binky Brown,” later wrote that “Binky” launched “many other cartoonists along the same path, myself included.”

Art Spiegelman, who has long noted that Green’s work paved a way to his Pulitzer-winning graphic novel “Maus,” said in a phone interview that he used to collaborate with Green, before “Binky Brown.” They bonded over having both taken “the same shoddy mail-order comics course as kids.”

But Green, Spiegelman said, “had access to a brain that didn’t work the same as other people’s.” Cartoonists like Charles Schulz and Jack Kirby had long worked autobiographical details into comics, tucking them inside the adventures of Charlie Brown and Captain America. “But Justin was just showing his innermost shames, his embarrassments, desires, in a way cartoonists just didn’t back then. He was writing out loud the stuff you wouldn’t say in a small party of friends.”

Whether intended or not, his fingerprints on autobiographical comics would eventually be evident on Alison Bechdel’s “Fun Home,” the memoirs of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, the dreaminess of Jim Woodring, the alt-weekly strips of Lynda Barry — and on and on.

Chris Ware, the celebrated Chicago-area cartoonist whose own autobiographical comics are as precise as Green’s looked frantic, said Green turned himself “inside out on the page so remorselessly the reader was forced into not only doing the same, but seeking some sympathetic psychic space with the seemingly self-taught, jumbled-yet-clear, I-had-to-draw-it moments he committed to paper. Sadly, relief was scant, especially for himself.” The couple of times they met, Green offered “encouragement and praise at an early moment when I least deserved it — but when it meant the most.”

Green became known for a personal warmth that seemed at odds with the angst he would spill across a page. “I think he helped people so much partly because it helped him to forget his own anxiety,” said daughter Julia Green. “He was always in turmoil.”

His OCD and raft of anxieties meant “he was never comfortable,” Tyler said. “He had, like, a script he would follow just to get daily tasks done. He was very kind and deferring to people. He learned to navigate spaces to manage his anxieties. He would always make a nice presentation of himself. But he would not comb his hair and his clothes — no joke, every single piece of clothing that Justin owned had paint or an ink stain on it.”

He grew up with servants and cooks, the son of a successful industrial realtor. He was a nervous kid. His father would send him into businesses in the Loop to collect back rent. On his first day of school in Highland Park, his mother dressed him a Brooks Brothers suit, and the teacher sent him home with a note: “Your son is hopelessly overdressed.”

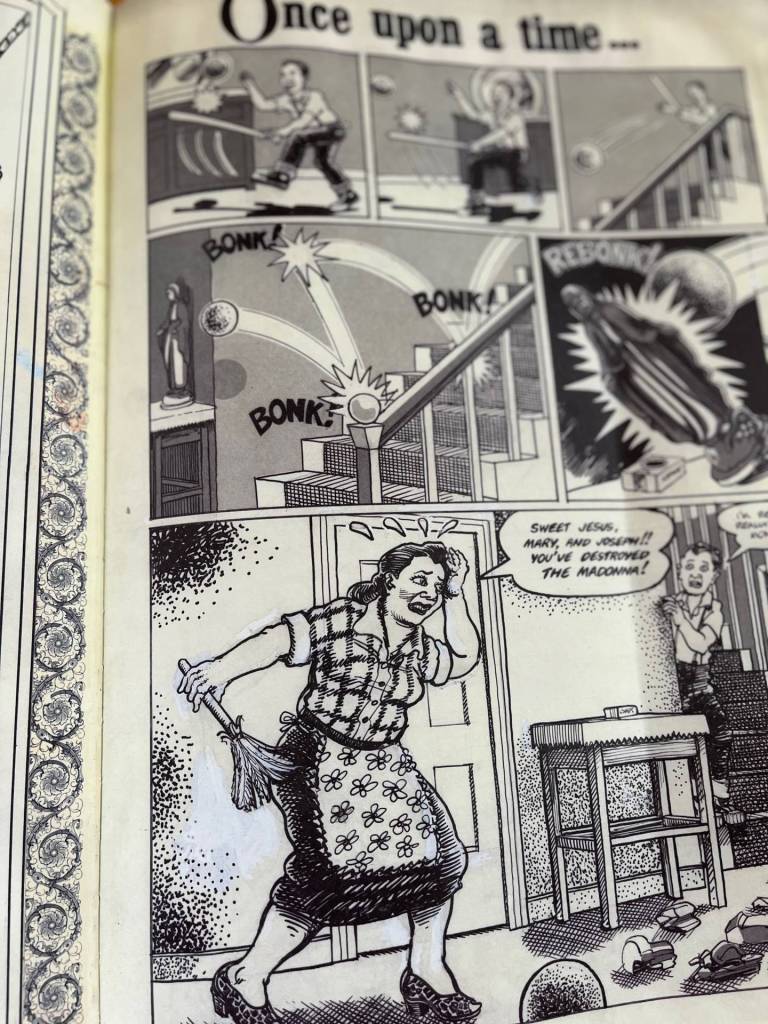

A page from “Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary,” published in 1972 by Last Gasp. (Christopher Borrelli / Chicago Tribune) Green lost himself in comics, favoring the art of comic-book ads and roughly-drawn funny-animal comics like “Peter Porkchops” over superhero books. He once wrote that after the local convenience store where he bought his comics was destroyed by fire, no museum could ever hope to offer “as much delight as that brilliantly colored comic rack.”

He attended the Rhode Island School of Design, then for a short time Syracuse University, but left for San Francisco and the lure of the 1960s, the hub of underground comix. He would become a staple of that small world, his work drawing on Dick Tracy, Crumb, E.C. horror comics and graphic design of advertising, finding its way into comics with names like Yellow Dog, Young Lust, Snarf, and back in Chicago, Bijou Funnies.

A decade later, he met Tyler in San Francisco. Being a fan, she sought him out. They were both Chicagoans, and a romance developed. He told the Tribune in a 2018 profile of Tyler that they realized they first ran into each other years earlier: “I was driving the 151 bus in Chicago in 1968 … I picked up Carol and her brother and kicked everyone off the bus and drove them to Wrigley.” As Tyler said, “CTA drivers then were in the 50s and overweight and here was this adorable, young driver. Of course I remembered him.”

They got married, and for the past few decades lived in Cincinnati, Tyler’s studio occupying the top of their home, Green’s occupying the ground floor. There he continued what he had been doing in San Francisco — hand-painting signs for a living.

He got so good that he could craft a variety of fonts from memory, with nothing but a wet brush and a clean building facade. “Comix were always his identity,” Tyler said, “but it wasn’t like today. Then you might get a comic into a magazine or a book maybe, which then showed up in a headshop. But there was no money. So he became an exquisite sign painter.” He painted signs (and occasionally made a new comic) until he died.

Green is survived by Tyler, their daughter, Julia Green, and Catlin Wulferdingen, a daughter from an earlier marriage, as well as two sisters, Eve Green and Karin Moss.

His last request, his family said, was for the large career-spanning retrospective of his work that eluded him in life; indeed, last summer, during a vast MCA Chicago history of cartoonists in the city, neither Green nor Tyler were included. So his daughter Julia is now planning a Justin Green retrospective for fall, at her gallery in Cincinnati.

Green would often wave off the claims that he pioneered the most contemporary and prolific genre of adult comics. He would point out that he had been just as influenced himself by Philip Roth, James T. Farrell’s “Studs Lonigan” and “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” But he was flattered by his place in the medium that dominated his childhood. In an afterword to McSweeney’s 2009 reissue of “Binky Brown,” he wrote:

“I am especially humbled and vindicated by the thought that my comic book was part of the soil from which Art Spiegelman’s ‘Maus’ sprouted. For that alone, I’ll die happy.”

This story was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on April 29, 2022.

-

An 1853 law gave Black people 10 days to leave Illinois: You were never taught this history

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneIf you were a free Black person moving through the antebellum United States, at least in theory, you faced a handful of stark options: Settle in a slaveholding Southern state, venture out into the vast unknown plains of the West, move into abolitionist New York or New England, or take a chance on one of the supposedly free states of the Midwest.

By 1848, according to the Illinois Constitution, slavery did not exist within its borders. On the other hand, some Illinois newspapers ran notices identifying runaway slaves so former owners could find them. And in 1853, a 26-year-old state representative from southern Illinois named John Logan — whose family had a reputation for grabbing runaway slaves — introduced what would eventually pass and become known as the Logan’s Black Law.

Its message was loud: From here on, Illinois did not welcome Black people.

For the 12 years the law remained active, any Black person who migrated into Illinois had 10 days to leave; if they didn’t, they were fined $10. And if they couldn’t pay, they were subject to being sold at auction. In return for covering their fine, the purchaser could demand labor, without pay, for however long a judge decided.

The case for the law sounds familiar in 2022: Supporters claimed Black people would be a drag on the Illinois public dole, generate crime and take the jobs of white people. Neighboring Ohio and Indiana began passing similar laws that said Black people couldn’t testify against white people, that refused Black people the right to vote and that excluded any Black child from getting a public education.

The funny thing, in Illinois, is those new laws brought Black residents together.

Ten months after Logan’s Black Law passed, in Chicago, in a hall near Randolph and Clark streets, Black Illinoisans from across the state gathered for the first time. It was the Chicago edition of the so-called Colored Conventions Movement of the 19th century, which started in Philadelphia in 1830. The Black population of Chicago was small then. In 1837, there were only 77 Black residents; but 20 years later, there were just 7,500, statewide. The Black Law became an existential threat to the future of Black Illinois.

Delegates to the convention wondered openly if they should just leave the country. The proposal was nixed, and instead, they organized and protested. But they also discussed emancipation, education, labor, health care, the courts, voting rights and women’s rights.

Even as slavery remained legal throughout the South, they planned a different future.

Or to put it another way, before Black Lives Matter, Black Power, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois and the NAACP, there were the Colored Conventions.

Kate Masur, the Northwestern history professor, chats with students Marquis Taylor and Mikala Stokes. (E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune) You’ve never heard of them.

Probably most of us have not, said Kate Masur, an Oak Park native and history professor at Northwestern University who specializes in the United States before 1900. “I would venture to say, what Illinoisans know about the history of African Americans in Illinois begins and ends with the Great Migration. What’s taught in classrooms about the 1840s and ’50s? Slavery. Even now I hear, ‘How do I not know this history of the Midwest?’”

So, two years ago, Masur and a handful of Northwestern undergraduates and graduate students started work on an online exhibition of sorts, part of an even larger archive that now spans several universities and museums, to document the radical importance of the Colored Conventions movement, one of our first nationwide conversations on race. Recently launched, their website (coloredconventions.org/black-illinois-organizing) does not have the sexiest title: “Black Organizing in Pre-Civil War Illinois: Creating Community, Demanding Justice.” But its history is more accessible than academic and its intent is ambitious: No less than a reframing of Black Illinois itself.

There are two dozen profiles of Black residents in the 19th century, and histories of local Black churches, and vintage photographs of early Black communities, and data visualizations of settlement patterns of Blacks in Illinois, and charts tracing the growth of independent schools, and interactive maps that reveal where the Underground Railroad operated within Chicago — all of it centered on the conventions.

And that’s just the Illinois website.

“In terms of Black activism, we have an overly prevalent cultural image that real Black organizing only started in the 20th century,” said Mikala Stokes, a Northwestern Ph.D. candidate in history who worked on the project with Masur. “There’s a lack of understanding of how many Black people there were before the Civil War who had their freedom. The vast majority of Black Americans were enslaved, but that free population was not insignificant, and they were asking a question: What does it mean to be free and Black in a slaveholding republic? They were reaching hearts and minds out there.

“So much of the national focus was on the anti-slavery debate — yet as the country heads toward the 20th century, there’s also talk of Black citizenship, conversation about how African Americans helped build the country itself, there’s an argument about whether the U.S. Constitution is pro-slavery, and if our policies are incongruent with founding American principles. The delegates in Chicago are making hypocrisies stand out. The idea that African Americans are American — that doesn’t form out of thin air.”

The Colored Conventions Project started in 2012 with P. Gabrielle Foreman, a Hyde Park native and African American Studies professor at the University of Delaware; she’s now at Penn State, and co-director of the Center for Black Digital Research. A decade on, at least 2,500 academics have worked on the project, creating 18 online exhibitions.

“Why have we not heard enough about this early activism?” asked Foreman in a phone interview. “I think it’s because it’s not the kind of uplifting U.S. history that allows for the nice beautiful tidy arc that ends in something good — like the ending of slavery. These conventions were taking place in nearly every U.S. state and territory and instead of ending triumphantly and decisively, you read about the people who organized them, and their struggles, and what they argued about and you have to wonder: Why we are still arguing for basic things Black people were arguing for 70 years, in the 19th century.”

The project began with one of her classes, she said. “We were studying the networks of Black activism, and someone said, ‘Why aren’t we focusing on women at all here?’ Which was a good question.”

Black women had been instrumental in organizing the conventions, so the class voted to continue studying the history of the conventions. While Masur was working on a book that touched on those subjects — “Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction,” published last spring — she was “taken with the depth of documentation that Gabrielle’s project included,” which led to Masur teaching a Northwestern class on the Convention Movement.

The exhibit that Masur and her team recently completed is a model example of what her project intended, Foreman said, not merely a snapshot of a movement but something that captures a time. “Really, it’s allowing us to see how questions of Black rights and white supremacy, which are so much a part of American history, were not just Southern or Northern issues but also central to the growth of the Midwest.”

Among the more than two dozen families and delegates profiled in the exhibit, many were born enslaved, coming into Illinois from Kentucky and Missouri, settling near the Mississippi River. They became farmers and blacksmiths and barbers. Looking to create community, they also formed schools and churches and built businesses.

Chicago was not the hub of these early settlements, and yet some of the delegates laid the framework for the Chicago to come. James Bonner, an early Chicago activist who served as the Cook County delegate to the convention, was instrumental in building a new home for Quinn Chapel in what became the South Loop; it’s still the oldest Black church in the city (though the chapel that Bonner helped establish was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871). Mary Richardson Jones — whose home hosted Frederick Douglass when he was in town (including when he attended the convention) — sheltered fugitive slaves, raised money for the families of Black soldiers, created a Chicago literary society and served as a mentor to a much better-known Chicago activist, Ida B. Wells.

“I was really surprised by the interconnectedness of these people then,” said Marquis Taylor, a Ph.D. student who worked closely with Stokes on laying out the narrative of the Chicago convention itself. “Though they were facing these laws at home, they had railroads, and they were very much concerned about what was happening across the country. You had people from all over coming to the convention here. There’s a letter from one of the conventioneers apologizing to Frederick Douglass that he was going to have to leave Chicago early because he was due for yet another meeting in Nebraska.”

To research these lives, the team dug into archives of small-town historical societies across the state, plus personal letters, census records, obituaries, church newsletters, newspapers and marriage records.

Valeria Lira-Ruelas, a junior history major at Northwestern who worked on the project, said she grew up around Rockford where she was “taught almost nothing” about the history of Black Illinois. “I was in a lot of AP courses and they pretty much stick to the testing, and so you get nothing like a nuanced history. I mean, when I was a freshman (at Northwestern), I read (King’s) ‘Letter From a Birmingham Jail’ — and I didn’t know he went to jail! I was surprised to learn some people didn’t like him! The nice thing is you get a sense these days of a push towards a more complete history.”

Indeed, Masur particularly hopes to see their website being used in classrooms across Illinois (and has already started to work with history teachers at Evanston Township High School).

“An exhibit like this could just sit there, I guess,” she said. “Or it could get worked into curriculums. Then you might start to see a shift in the way people think of the early history of this state and African Americans. When it comes to the story of Illinois, it doesn’t have to be about just Abraham Lincoln.”

This story was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on April 15, 2022.

-

The Kanye West in ‘jeen-yuhs’ on Netflix begins with the Chicago Kanye — already arrogant, unsatisfied, hard at work creating music

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneA filmmaker plays fly on the wall to the world’s biggest pop stars.

Gathering mountains of footage, some of it revealing, nearly voyeuristic.

And so, for myriad reasons, it goes unwatched, for many, many years.

That’s true of Peter Jackson’s “The Beatles: Get Back,” which debuted in November, assembled from hours of material that director Michael Lindsay-Hogg shot in early 1969, capturing both the recording of “Let It Be” and the splintering of the group itself.

But that’s also true of “jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy,” which unfolds over three episodes on Netflix this month. It’s constructed of years’ worth of footage that Chicago filmmaker Clarence Simmons — with directing partner Chike Ozah, credited as Coodie & Chike — gathered of Kanye West in the nascent days of his career. If “Get Back” documents a season of unease, dissolution and hurt, “jeen-yuhs” is a season of promise and hurt.

But mostly, these are films about creating.

As in, the physical labor.

These are not movies about personalities or internal disputes or the cost of fame or hollow claims of greatness, but rather what it takes to sit down and get something made. The grind, the hard part, the day-to-day ups and downs it took to create the music of the Beatles and Kanye West. Both films will be discussed for years, for endless reasons, but their value has less to do with breakups, breakdowns or biographical insights than a forensic patience, a willingness to watch and watch, then watch some more, that most mysterious of qualities — creativity. Which means, both films are long. Collectively, they’re about 12 hours, though not because they’re long-winded. But because watching creative people actually make something — that’s rarely fast, inspiring, pretty, obvious.

Or sensical.

I had a friend who taught film school. For years, the first thing his freshman had to do was watch “Ed Wood,” Tim Burton’s beautiful 1994 portrait of the Worst Director in History. He did this because it was a reminder that vision and talent are only part of being creative. What if you don’t have talent, ideas or even competency? Does creativity only belong to the successful? Should you stop? The truly creative soldier on, and the Ed Wood in that movie (played by Johnny Depp, with boundless optimism) is all headlong momentum, even as everyone working with him sighs and groans and doubts.

In Quincy Jones’s upcoming memoir, “12 Notes: On Life and Creativity,” he remembers his South Side childhood and routinely climbing through the window of a rec center to play its piano. “I tried to mimic sounds I had heard at the old Baptist church I attended. … But when I ran out of tunes that I could remember, I resorted to playing whatever I was feeling.” In Bob Odenkirk’s “Comedy, Comedy, Comedy, Drama,” another upcoming, locally minded memoir, a former girlfriend recalls, back when he was writing comedy and roving show to show, Chicago to Los Angeles, his single-minded “super focus did not help build a relationship.” Let’s not confuse obsessiveness and drive with creativity, but they do live in the same cul-de-sac.

I swear, for the first three hours of “jeen-yuhs,” Kanye West is never shown relaxed, just sitting back. He is always restless, moving, hunched in chairs, at mixing boards, at home, T-shirts and takeout containers strewed about because he only works, to the eventual (and infamous) detriment of everything in his life. Yet in some of the film’s most charming moments, before he’s even recorded an album, he’s shown barreling through record companies, popping CDs onto the nearest trays and rapping for whomever happens to be in the room. It’s not just that he’s a man in need of a stage, but that, in a more pragmatic sense, he’s testing new material on anyone around — he’s fine tuning.

I have a thing for this, for art that captures the boring stuff about art.

Also known as, making art. Still, I like to see the coming-together, I like to watch the sausage getting made. I love the tedium. So do you. Some of the most popular videos on TikTok and YouTube are basically industrial films — assembly-line tourism, a box being constructed, a candy cane being forged. Even the best season of “Curb Your Enthusiasm” was less about the headaches and arguments that led to a new, improved “Seinfeld” finale, than about a million little conversations, casting decisions, promises.

The salacious, heated stuff usually bundled into showbiz memoirs, Oscar biopics and narrative works about the creation of art and rise of great artists — I like that, too. Those ubiquitous documentaries that purport to dig behind the music — it’s fine, it’s fun. (Yes, I plan to watch “Pam & Tommy.”) But that’s another breed. I’m talking about films and books that approach creativity like it’s Take Your Audience to Work Day. Which, of course, require some degree of renown and hubris to even expect attention. Lillian Ross’s “Picture,” her classic 1952 nonfiction account of the making of “The Red Badge of Courage,” wouldn’t have been possible if John Huston wasn’t on a historic roll — “Maltese Falcon,” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” “Asphalt Jungle,” boom, boom, boom — begging for documentation. The popular podcast Song Exploder is at its best when exploring the dull, practical decision-making from artists who wallpaper our world — Common, U2, Metallica. “All That Jazz,” Bob Fosse’s 1979 semi-autobiographical film isn’t about inevitable success, but make-up tests, rehearsals, writing, thinking; only after that is it also a dramatization of Fosse editing the film “Lenny” while staging the play “Chicago.”

Again, there’s a degree of hubris in assuming we might care.

“Get Back” takes this to a logical extreme: If you could spend hours in the studio just watching any recording act in history, the Beatles would be a lot of people’s first choice. Which even the Beatles knew when they gave permission for a filmmaker to capture nothing much: songs endlessly retooled, late-day exhaustion, piano plinks that evolve into classics, Paul strolling into work in the morning, everyone wondering what’s for lunch and many, many thousand yard stares that (knowing what we know now) look like the earliest glimmers of “Band on the Run,” “Imagine” and “All Things Must Pass.”

Like any historical document, “Get Back” seems to hold both the past and the future at once. Jackson’s film may be the most intimate portraits of creativity we have because it is so willing to present us with nothing much at all. Just that boring struggle to create.

In “jeen-yuhs,” Kanye West — who just had his name legally changed to Ye — is so certain of his creative importance, it’s an ongoing joke among friends that Coodie is following him before anyone knows him. But Kanye has good instincts here. So does Coodie — a Chicago stand-up with aspirations of making a music-industry take on “Hoop Dreams.” He captures dental appointments. He finds Kanye at parties where everyone is socializing but Kanye is off by himself, focused and working on his record. Odds were, Coodie would be gathering material for a “Hoop Dreams”-like portrait of disappointment. Of course, he got the opposite. About midway through “jeen-yuhs,” the footage, and story, changes, feels more familiar. There’s success, then, inevitably, the creep of peak Kanye cringe looming, and so we watch, again, the kind of material that will eventually, some day, find its way into an Oscar biopic. George Bush not liking Black people, Taylor Swift, that 2020 presidential run, Donald Trump, all those Kardashians.

For nearly three hours, “jeen-yuhs” avoids the worst of Kanye West by avoiding the downfall that movies about artists eventually turn toward. But then, it also never becomes the cheap flurry of headlines and poetic montage of dramatic creating that tar movies about artists. Even after the craziness takes center stage, Kanye is rarely shown not creating. He’s forever the one leaning in, finishing a song, going over a design for his fashion line, sketching out ideas for artist Takashi Murakami to work onto new album covers. There’s a Fellini-esque swirl late in the documentary, at Kanye’s ranch in Wyoming, a large sound studio-like warehouse, not unlike the one in “Get Back.” Justin Bieber is recording a refrain in the next room. A live band is tinkering on a small stage. A Kurosawa film is being projected behind them. Meanwhile Kanye is on the phone with producer Rick Rubin, discussing a visit to the studio of sculptor Tina Frey.

Maybe that’s Warhol-esque swirl.

By this point in the film, though, Kanye is so popular and impenetrable, Coodie doesn’t have the access he once did. And access is the key to many great works about creating art. Which is why intimate ones are so rare. I often tell friends to read Julie Salamon’s “The Devil’s Candy,” a painstaking 1992 book about the disastrous making of Brian De Palma’s “Bonfire of the Vanities,” but I always add a sad reminder that the access she had to that production was remarkable in the early ’90s, too. As much as Hollywood likes to sell the dream factory stuff, a film like Robert Altman’s “The Player” is so blunt about how sausage actually gets made — “It’s ‘Out of Africa’ meets ‘Pretty Woman!’” — there’s a protective urge to stick with the cheap flurry of headlines and poetic montages.

Coodie tells us in the narration that as Kanye takes off, he asks Coodie to back off. He tells the filmmaker that he’s playing a role now, and all that earlier stuff, that’s too real.

Ironically, it’s now a humanizing portrait of an artist who could use some salvation from caricature and persecution — self-inflicted and not. You want to know what it’s like to be an artist? Watch Kanye stand in the street outside a record company, trying to catch a second with an executive. Hear an A&R guy ask, with implied mockery, how Kanye’s record is coming. Kanye was not an artist then but a producer, with a reputation for being meticulous, arrogant and self-doubting. “It’ll never be finished,” Kanye said softly.

He’s not lying.

We watch him reworking lines, beats, cadences, phrasing, adjusting, head down, burying himself inside the work for long periods, adjusting again. He describes Jay-Z’s recording process as: bunch of rappers come to the studio, a week later the guy leaves with a new record. He says it with a laugh and a hint of jealousy. He can’t leave well enough alone. The second of the three films begins with his 2002 car accident in Los Angeles, then finds Kanye, six weeks later, in a hotel room, jaw nearly wired shut, still working, the room a landfill of recording gear, song outlines, half-eaten meals. Among the many things “jeen-yuhs” is saying about creativity is the need for support, mental and otherwise, and for a long time, his mother leads that charge. She is his perspective.

One of the film’s most touching scenes is a late-night visit to Donda West in her Chicago apartment. She tells her son: Stay on the ground and you can be in the air at the same time. He listens, but as with “Get Back,” the circle gets progressively too crowded, too loud. Kanye becomes obsessed with whether he is a genius. Some friends push back.

Not for you to say, they tell Kanye.

To which Kanye says … nothing, not at first. Why bother responding? He has a studio of his own. There are scenes in “jeen-yuhs” where more famous rappers grow silent and intimidated by his startling promise. Still, his need for validation remains bottomless. Not a surprise, but one in which Coodie & Chike find room for a more poignant conclusion: Whatever genius is there, whatever work he creates, is inseparable from Kanye, good and bad, arrogant or honest. Speaking of Fellini, it’s nearly a salute to “8 1/2,” itself a portrait of artistic sausage production. Marcello Mastroianni plays a great director whose film is falling apart, until he realizes he is nothing without those who love him. He shuts down production and accepts the failure, because failure, in the end, is part of creation.

This story was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on Feb. 18, 2022.

-

‘End of an era’: Once a staple of the holidays — and middle class life — the last Sears department store in Illinois closes Sunday at Woodfield Mall

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneSo it has come to this.

The last Sears department store in Illinois, which closes Sunday in the Woodfield Mall nearly a century after the retailer opened its first stores , looks very, very… beige right now, in its final hours. Like beige on beige. Like the color of back-to-school Toughskins in 1974, the color of your uncle’s Corolla in 1982 and the color of linoleum at the DMV in any decade.

It opened the same day that Woodfield — named for Sears executive Robert Wood and department store magnate Marshall Field — opened in 1971. It was the largest Sears then, boasting 416,000 square feet of sales floor. From the looks of it in late 2021, it’s hard to imagine anything changed in 50 years.

The exterior now resembles a vinyl-sided carport in a crumbling neighborhood, surrounded by walls of Flintstone-esque faux stone. The interior is still organized by old familiar clusters of merchandise — wrenches, mattresses, baby shoes, never-pleated slacks — except everything looks slightly soiled, stripped of its freshness. Even the smell of rubber that once sweetened the power tools section has been stripped. The video monitors of pricey displays are now dark and askew. The Samsung showroom is pulled away from its moorings and its appliances are gone, leaving bouquets of frayed wiring.

Large bins hold landfills of mannequins.

The home furnishings department is streamlined to a single ironing board and, as if the retail universe were winking, a single damaged doormat that simply reads “Good Bye.”

Should you visit the last Sears department store in Illinois — and if you do, bring a few tissues, as this is a tearful story — you’re not reminded of a once thriving consumer destination but one of those roadside stands in a dystopian thriller, the kind where drifters sell whatever scraps they can salvage from the post-apocalyptic landscape.

Signs hang from rafters:

“EVERYTHING MUST GO!”

Above the sporting goods department, a banner in one-zillion-inch type:

“STORE CLOSING.”

Like we need reminding. There are a handful of tennis rackets, a few Little League gloves, two NordicTrack slaloms and far too many packages of ping-pong balls. That’s the sports section. Around the corner, in time for the holidays, the loneliest toy department ever. All three shelves of it. A plastic NASCAR helmet. Two Star Wars action figures. Unicorn soap. One soccer ball. Something called Foodie Roos Chips (“I look, smell and feel like my favorite food”).

If you are of a certain age, you will wince. When I was a kid, part of every autumn revolved around spending way too much time pining over every page of the monolithic Sears Christmas Catalog, circling ideas for Santa.

No wonder a woman wandered past scowling, shaking her head, looking awed by the desolation and grieved by the loss. She leaned into an elderly man she didn’t know who was sitting on his walker, taking in the wasteland before him. “A shame,” she whispered.

He nodded.

“End of an era,” she said.

He nodded.

She was Angie Sanchez of Bolingbrook, and she came to catch a glimpse before it was gone. “I grew up with Sears,” she said. “Everyone I knew grew up with Sears. You would come at Christmas, partly because of the decorations alone. You know, their Christmas tree. There was like real joy here once.”

Beside her were cardboard bins of loose ornaments, inelegantly bundled under plastic wrap. The only Christmas trees were table top and broken, going for a few bucks. Sanchez was the fourth in a family of 13 kids. Her father worked for Inland Steel and supported them on a welder’s salary.

“I wonder what’s going on in this country,” she said. “Just the rich are favored. We forgot what we had — even if it was just Sears. We forgot to value things, and now we have… Amazon.”

Indeed, once, the first floor of your Sears department store smelled like popcorn.

The display of its off-brand Atari consoles was a convention of neighborhood kids.

I remember going with my grandfather to buy a new washing machine and coming home with AC/DC’s “For Those About to Rock, We Salute You” on vinyl. I remember waiting at the oversized merchandise window for a ping-pong table. I remember shopping for school clothes and finding a sea of sweaters that looked like the design team had quit 25 years earlier. I remember Sears jeans that looked like slacks. I remember a Howard Johnson across the street from Sears and baskets of clam strips.

I recall the very specific American theater of a Sears department store, which had a kind of shared middle class identity, one that was whittled away, partly by the convenience and price of Walmart and Amazon, partly by wages not keeping pace with productivity, partly by the decline of unions, shared facts and so, so much more. A large American middle class made Sears and, in exchange, Sears provided Kenmore and Craftsman, Toughskins and Discover. Whenever I see a parody of a family picture on Instagram, I think of quasi-beatific Sears portraits with mottled backdrops hanging in homes. I think of tens of thousands of Sears kit houses still standing around the country.

All relics now — like the metal filing cabinets and office copy machines in the Woodfield store, hauled out of the back offices, plopped onto the floor and slapped with price tags.

Besides, Sears is not even really Sears anymore — after a long decline and bankruptcy in 2018, it was swallowed into the larger Hoffman Estates-based Transformco, which also owns whatever remains of Kmart. A Transformco spokesperson sent a statement that the Schaumburg store is actually not the last Sears in Illinois, that there are still 11 remaining in Illinois, notably its Sears Hometown stores.

That said, it is the last Sears department store in Illinois, and again, to a shopper of a certain age, that’s the same as the last one. At its peak, Sears, once the largest retailer in the country, had 3,000 locations, so naturally this Woodfield store is far from alone. Also dead after Sunday are Sears department stores in Pasadena, California; Maui, Hawaii; and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Long Island recently lost its last Sears department store; Brooklyn loses its last Sears on Thanksgiving Eve.

Indeed, seeing a Sears department store still serve as the anchor for a large mall right now is like a window into just how stormy and unmoored from the 21st century the American shopping mall has become. Sears sits at the south end of Woodfield, while JCPenney is at the northern end; Macy’s and Nordstrom occupy port and starboard sides.

The day I visited, about a week before closing, the ship was mostly submerged.

A serving bowl with four papier-mache apples was going for $5. There were a lot of lampshades and not a single lamp in sight. I remembered I needed a phone charger but all they had were the cords for Apple devices several generations old. But they had stacks of “ultrasonic” humidifiers and a few candlesticks. Diamonds were 80% off.

Behind the jewelry counter stood Marilyn DeAngelis.

She’s 77 and has worked here for 22 years. She was one of the “cosmetics girls” for a time, she said. She’s worked all over the store, all different positions. As she talked she tried clasping a thin necklace around a small display. As if presentation still mattered. As if 60% or 80% off wasn’t its own enticement.

At last, she caught the clasp, draped the chain on the stand, slid it back into the glass case and looked up. She smiled sadly. She’ll have to find a new job, she said. She liked this one. She didn’t have a choice. It’s too bad, all of it. She’ll miss the Christmas decorations and even Black Friday wackos. But mostly, she’ll miss the Sears department store. “Then again, once, it was just bigger.”

This story was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on Nov. 12, 2021.

-

On the same day as the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, a wildfire in Wisconsin killed 1,500 people or more. You’ve never heard of it.

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribunePESHTIGO, WISCONSIN — On a weekday morning in late summer, at the corner of Front and French Streets, with the Peshtigo River at your left, and the town of 3,357 spread before you, nothing stirs. The sun rises and the hours pass and still nothing much moves. The streets seem wide and empty. A backdoor slaps its frame. A breeze puffs and the celebratory banners stretched across a bridge flaps and straightens out long enough to make out an illustration of lapping flames. It’s a reminder of the upcoming Peshtigo Historical Days. Which, this year, marks the 150th anniversary of the total destruction of Peshtigo. It’s what Peshtigo, just north of Green Bay, is known for: being flattened by fire, becoming hell on earth, for one night only, in the late 19th century.

On Oct. 8, 1871, even as the Great Chicago Fire roared 250 miles south, the arguably greater Peshtigo Fire — still considered the deadliest fire in United States history — leveled more than 1 million acres, flattened 16 neighboring towns and killed between 1,200 and 1,500 people.

Some historians insist that figure is probably a thousand victims too low. Eyewitness accounts described fireballs, mass drownings, an atmosphere marked more by flame than sky, a veritable hurricane of fire, coupled with actual tornadoes of flame that lifted entire buildings from foundations.

Stand in the center of Peshtigo and try to imagine this.

You don’t come close.

One day Peshtigo was a steadily growing company town, spurred to success by railroad and lumber tycoon William Ogden, the first mayor of Chicago, who owned much of Peshtigo.

The next day, after a firestorm that lasted only two hours, almost nothing remained.

“I’m old enough to have known survivors,” said Cubby Couvillion, 95, the town historian. “I recall well a lady in our neighborhood, at our backyard fence, leaning over, talking, telling me about that night, how her mother gathered up a suitcase, her father said it was time for the family to head to the river, how a woman crossed their path in a nightgown, running down the road, screaming, because her head was on fire.”

So intense was the inferno that entire families vanished.

A father, cornered by the fire, slit the throats of his own children. Among the few things that survived the fire were firsthand accounts, preserved in diaries, by local historians and in journals. Cattle trying to escape the flames stampeded residents who escaped into the river. The 1870 census reported 2,000 residents in Peshtigo. A year later, the fire had killed at least 800 who lived in the small downtown area alone. The fire was so destructive that years later the U.S. military, just prior to entering World War II, studied it in the hopes of re-creating its conditions in German cities.

And yet, you have never heard about any of this, have you?

You’re not alone.

When vacationing Chicagoans hear the details, they sometimes apologize in revulsion, said Helene McNulty, a volunteer at the Peshtigo Fire Museum. “They get physically upset at how much attention the Chicago fire got and how little is known about this far worse fire, which happened so close, at the exact same time.” The way she says “Chicago fire,” you imagine air quotes. The Great Chicago Fire flattened three and a half miles and killed 300 — a perversely mild tally compared with what happened here. So Peshtigo refers to its fire as “The Forgotten Fire.” Being destroyed then overshadowed — that’s its identity. They have a Forgotten Fire Winery. “Of course it’s unusual to be fire chief here,” said Mike Folgert, “but as I say, ‘It didn’t happen on my watch.’”

Cubby Couvillion, 95, sits near the mass grave in the Peshtigo Fire Cemetery, in Peshtigo, Wisconsin. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune) Walk a few yards into the cemetery holding many of the residents killed by the fire and between the aging, pocked headstones fading in sun and weather, there is an arrow of a sign that reads “Mass Grave,” directing you down a sloping hill. At the bottom is a plot, larger than the typical burial patch, marked with a single small white painted wooden cross. Here rest 350 victims, many of whom were killed in the Peshtigo Co. boardinghouse owned by Ogden. What’s actually buried, though, are parts of bodies, bones, ashes. Intact corpses were tough to come by.

Fitting a town that exists so close to its death, few commemorative markers around Peshtigo mince words or sugarcoat what happened in 1871. At the Fire Museum, located beside the cemetery, there is a mural of the fire painted on the back wall that partly depicts a man burning to death while simultaneously being trampled by a horse. With a wince, McNulty said that when she was growing up here, her siblings used the site of the mass grave as a sledding hill. It’s not hard to picture teenagers lingering amid all of the gruesomeness.

Here lies the Kellys, who got off easy, losing one child and the patriarch.

Here lies the Lawrences, who took shelter in an open field, only to be killed by a fireball.

Here lies the Mellens, whose 19-year-old son carried his two siblings into the river to avoid combustion, only to emerge four hours later with the siblings in his arms, now dead of hypothermia.

Here lies the Lemke family, whose patriarch survived but, as the grave marker explains, fled and looked back to realize that he’d been separated from his family, who were now “burning furiously.”

As I poked around, a man in a Chicago Dogs T-shirt said it was crazy how few people in Chicago seem to know anything about Peshtigo. Plus, he’d heard the whole thing was caused by a meteorite.

Actually, no one knows for certain what caused the Peshtigo fire. McNulty says that she tells visitors to the museum it was likely a combination of railroad workers clearing brush during a particularly long dry season, a fast-moving cold front that fanned flames already smoldering — or likely some combination of those and more. “Then they look at you and say, ‘Yeah, but tell me how it really started.’” They want to hear a story about a cow kicking over a candle.

Or a match landing in a bale of hay.

Something apocryphal and clear.

A number of accounts place a degree of blame at the feet of Ogden himself, without quite implicating him. In 1871, Peshtigo was fast becoming a center of the Midwest lumber industry. Thanks to Ogden. He had built a lot of what resembled Peshtigo in 1871. Local farmers, many of whom were relatively new immigrants from Northern Europe, saw opportunity here and began clearing more and more land, often using fire. Geographically, the town was nearly perfect. Ogden had bought an existing mill here 15 years earlier and cleared large swathes of forest, transported it down the Peshtigo River to the mouth of Green Bay, then south on Lake Michigan to Chicago. Without Ogden, Peshtigo “would be a wide place in the road,” said Couvillion. On the other hand, he added, Ogden also offered a bonus to his workers if they finished new railroad tracks by 1872, to speed lumber traffic to Chicago. As the New York Tribune explained after the fire, Peshtigo was created solely for “one purpose, to make money for its founder and keep up the lumber interstate.”

Yet fires had been raging across the upper Midwest throughout September, in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin; indeed another vast fire in nearby southern Door County on Oct. 8, 1871, often conflated with the Peshtigo fire, was probably a separate blaze. Smoke grew so dense in Peshtigo harbor that foghorns routinely blew. Peshtigo, aware of these smaller fires creeping close, grew nervous.

Peshtigo, surrounded by dense forest, was geographically removed from its neighbors. It was frequently described by visitors as appearing suddenly in a clearing outside the pines. Roads were rare. By the time the fire reached Peshtigo, all communications to outside were choked. Residents reported a sound like an approaching train — not so different from how contemporary Midwesterners describe tornadoes. What followed, however, sounded closer to rolling waves, a tsunami of wildfires.

A Smokey the Bear fire alert sign sits on the roadside in Peshtigo, Wisconsin. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune) The inferno reached downtown on Sunday evening.

By morning, newlyweds were dead and infants were found alive beside still burning parents. The river was thick with drowned residents and farm animals. Families were found huddled in clumps, sometimes alive, most of their clothing burned away. One dead man was identified by his wooden leg — perversely, the only part of him that had not burned. Many survivors, having spent hours so close to flames, beneath a deep orange sky swirling with embers, reported being temporarily blinded. The Chicago Tribune, reporting from the scene, compared it to Sodom, Gomorrah and Pompeii. And Ogden, having lost a fortune in the Chicago fire, lost everything else in Peshtigo: his sawmill, factory, boardinghouse, railroad. He promised to rebuild, but never did.

The governor of Wisconsin, still aiding Chicago, redirected resources to Peshtigo.

Bud Lemke, 91, a descendant of the Lemke family nearly decimated in the fire, still lives on his great-grandfather’s farm. “He survived but his kids and wife burned and he had a hole burned into his stomach and yeah, his eyes burned out. And when he came back to Peshtigo, he had nobody to live with. He arrived from Germany. He had no one left here. And so he moved in with a generous family who lived on a nearby farm and whose house had miraculously not burned and so, on the anniversary of his wedding, my great-grandfather, he bought their farm! Then he gave it to them! They didn’t own it yet. He did it out of gratitude to the family. He paid $1,325. I often wonder where he got it. Probably from the donations given to survivors. But today, that family still owns that farm.”

Cubby Couvillion, 95, walks down the aisle of the Peshtigo Fire Museum. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune) The Peshtigo Fire Museum is something between a small town museum and an antique store that won’t sell you anything. What it is not is a museum about a fire. It’s housed inside a century-old church (now the oldest structure in Peshtigo). It became a fire museum in 1963, though many of the items that pass for artifacts were donated to fire survivors from throughout the Midwest and beyond. It’s more like a museum about turn-of-the-century lifestyles. Ancient ice skates. Dugout canoes. Giant bikes. Church hats. First-generation Zenith radios. Wooden classroom desks. Sewing wheels. A gun recovered from the nearby river after Peshtigo National Bank was robbed many decades ago (by a couple of guys from Chicago). One wall holds portraits of survivors, including the last living one, Amelia Desrochers, who died in 1966 at 100. It’s a museum about how ordinary life can become after tragedy. Chicago’s fire got the attention, but here is low-key poignancy. So generous were the donations that many survivors ended up with more than they had before the fire.

With a practiced singsong, the museum volunteers apologize to the trickle of tourists: There’s not a lot to see in here from the fire itself because not a lot of Peshtigo — almost no structures or possessions — remained the morning after the fire.

“It’s a miracle anything’s here,” McNulty said.

There’s so little they hold it in a single cabinet.

Remains of a watch. A kettle. A pie pan. A church tabernacle. Bibles. A business ledger from Ogden’s vault. A can of blackberries that fused with its tin cylinder, creating a kind of petrified black nugget. To be honest, McNulty whispered, some of this stuff comes from nearby towns flattened by the fire.

She waits in entrance to the church, answering questions from visitors and chatting with Paige Frappier-Potkay, a younger volunteer, who said, before working here, everything she knew about the fire, she heard from her great-grandmother. “I never got it in school,” she said.

Burned pages of a Bible and broken china are remnants on display at the Peshtigo Fire Museum. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune) McNulty sighed and nodded.

“I never got it in school either,” she added. “And I was baptized in this church! This fire, considering how much a part of our history it is, odd as it sounds, it’s never truly set in, all this time later.”

Peshtigo has two fire departments. One for the city, and one for the wider, forested area. The latter was established in 1964. It’s a volunteer department, with 25 part-time firefighters. When I asked Clarence Coble, town clerk (and volunteer firefighter), why firefighting in Peshtigo has never been more than a part-time profession, he made the universal gesture for money — he rubbed fingers together. Still, compared with the nearly 1 million acre Dixie Fire in California, he said — then leaned forward, punched numbers into a calculator, converting square miles to acres — they have less land to worry about. Since 1871, they have had other infernos — a hotel burned, another paper mill, a church. Jim Meyer, a volunteer firefighter, told me they just had a big worry of a fire but no one was hurt. When he said they “just” had a big fire, he meant 10 years ago.

Still, look around here, in every direction, it’s all pines, oaks — a dense canopy of trees.

Mike Folgert, the fire chief, says it’s a different time, of course. They still do controlled burns to clear the dead parts of the surrounding forest that could ignite, “but that’s very controlled these days.”

One hundred and fifty years ago, there was no fire department here. Today they have 911, they have nearby departments as backup. They have roads. “But there is drought and climate change — so we have the potential everyone has.” Which is what worries Kate Lenz, forestry team leader for the local Department of Natural Resources. “In Marinette County here, when we get into staffing and preparing each spring, I always dread the thought of a fire where I lose a couple of homes in my own backyard. The conditions are different here than you see out West — species of tree, health of the forest, the length of (wildfire) conditions last longer there. But yeah, there’s a concern anyway.”

Fewer residents live in downtown Peshtigo now than in the surrounding woods. Which is also where there are no fire hydrants. And yes, there are roads in these areas now, but not necessarily the kind that make it easy to drive a large firetruck down — never mind turn a large firetruck around.

Lenz said, “Rural (fire) departments around here, they get a call on a Tuesday at 5 p.m., say, those volunteers might be out of town, working their day job. We’re still having pancake breakfasts around here to buy equipment. It should be a concern of anyone who has property or vacations up here.”

The Peshtigo River is narrow enough to imagine one thing about Oct. 8, 1871, with certainty: If you retreated here to the center of the waters, flames were still never far off. Anything alongside the river disappeared. Indeed, even now, there’s not much development on its banks. There are parks, a paper mill, several rows of modest homes a block away. That’s about it. A once-bustling harbor is closer to a small boat launch today. Peshtigo prides itself on being a town that rose out of its ashes — that’s partly the purpose of Peshtigo Historical Days. But the town lost much of its momentum in the fire and never quite boomed or bustled again. Those flames, in a way, never quit.

Cubby Couvillion has spent his whole life here.

When he talks about Peshtigo, he says in a melancholy sigh: “We live in a beautiful little city.” In the next breath he wonders if a layer of 150-year-old wildfire ash rests beneath the streets, even now.

“Imperceptible, but, you know, there.”

Leaving Peshtigo, headed east toward Michigan, you pass an old Smokey Bear, waiting with his shovel, ready. The sign notes that fire danger today is “LOW.” But it’s also placard, and it can change.

This story was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on Sept. 29, 2021.

-

Kanye West gives fans a remarkable, bonkers experience at Soldier Field ‘Donda’ listening party with Marilyn Manson, DaBaby and Kim Kardashian

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneEver find yourself in a place in life where you look around the room — as in, actually turn your head, survey the landscape, sigh loudly — and wonder how things ever got to this? How does one find oneself on a Thursday night in August, sitting in the rafters of Soldier Field, the Bears nowhere in sight, almost no one around you masked despite an ongoing pandemic, waiting hours for Kanye West to simply play a new record? Tickets — tickets! — for this “experience” (his word), for seats high in the Chicago sky, started at a low, low $185 (including Ticketmaster fleecing fees). That is, tickets to a listening of a new Kanye record, not tickets to a Kanye performance. And yet, it was an experience.

A remarkable, frustrating, bonkers experience.

Can we just get it over with and say the obvious:

Kanye West, sometime pride of Chicago, frequent albatross of American culture, son of the late Donda West (chair of the English department at Chicago State University), is our new Warhol, only restless, minus Warhol’s affectlessness, but with all the genius, ridiculousness, flatulence, ambition and daring that implies. So, naturally, “The Donda Experience” — as Kanye has called his occasional summer road show/test marketing/rumpus-room record hops — is also a kind of performance. Yeezus, it’s a performance.

More theatrical than musical.

Where do I even start?

Kanye rages against detractors (no surprise there). Kanye shows love to his hometown, Kanye sets himself on fire (wearing a stunt suit, and quickly extinguished), Kanye is surrounded by a quasi paramilitary. Kanye is met by a shrouded Kim Kardashian, who is currently divorcing him, wearing a gown of gothic white spectral opulence. Oh, and Kanye also plays “Donda,” his tenth studio album, which, as of midnight, had not been released yet. The Soldier Field “experience” was, it seemed, the homecoming culmination of a series of listenings Kanye has hosted since last year, including two arena-sized “experiences” in Atlanta last month. Chicago, though, received a spectacle.

At the Soldier Field 50-yard line — delightfully, with attention to peeling paint and ill-fitting curtains — Kanye had his South Shore childhood home rebuilt. Not a facade of the South Shore house. The whole damn thing. Then it was fixed with a large neon cross and placed on a hill surrounded by dozens of candles. Apparently, some people go to a therapist and some people reconstruct their childhood homes inside of an NFL stadium.

As Chicagoans Miles Baggett and Jasmine Robinson waited for Kanye to arrive, Baggett said that this being Kanye, he had no idea what to expect. Which is on brand. But you bought tickets, I said, you spent hundreds. Robinson said that she had seen Kanye live and she had no expectations, either. Which is part of the appeal. Who was the last superstar who truly left an audience wondering what’s next? “I mean, I was here to hear a record,” Baggett said, “but then Kanye put his childhood home on the field.”

Fans wearing Kanye-branded T-shirts — “I Miss the Old Kanye,” “Life of Pablo,” “Kanye for President 2020” — approached the stadium railing and snapped pictures of the house as if it were the Grand Canyon, admiring for a moment then turning on their heels to leave. Many wondered if he was already in the house, just waiting for the right moment. Kanye took the stage two hours late. A man sitting behind me said Kanye was likely hosting his monthly book club in the house, and he was really into it and didn’t want to ruin the vibe. Others spoke of the stage with the shades of nuance you would hear at an art opening.

Albert Luces and Tyler Heng had a theory.

Luces: “Kanye is giving a visual interpretation of how he feels. Like an artist does. The first experience in Atlanta, he was wearing all red because he was feeling like …”

Heng: “The devil!”

Luces: “Right, for the next one, he’s in black, a kind of purgatory. And now, he’s home, his literal home is right there, there’s a cross on it, he’s thinking about his mother …”

Heng: “His dead mother!”

Luces: “Donda, his dead mother. So I bet, for this show, he’s ascending with her to Heaven. I don’t know. It’s a theory I heard people say about these shows, they’re a set of shows in a way. Look, at the end of the day, Kanye West, being Kanye West, this guy knows how to deliver a visual stamp that’s always him. And that’s why I’m here, right?”

When the “experience” formally began, Kanye roved the front stairs of the house and danced along with the record, and I think he sang along with the lyrics but I couldn’t really tell because Kanye also wore a mask over his head for the entire show. Also, a choir wearing pentagrams walked in twos to the stage and circled the home. “DONDA! DONDA! DONDA!” blasted from speakers, like both a warning and prayer, modulated and remixed in countless ways. Screens flashed phrases reading “Alien Nation” and “No Criticism,” and a faux-cable news network reported “Breaking News” as a series of Biblical chapters and verses. Then a fleet — or funeral procession — of black SUVs circled the stage. Then paramilitary circled the stage. Then more trucks circled the stage. Then more paramilitary came. Then a fleet of vans circled the stage. Soon, the paramilitary, the vehicles, formed a circling prison wall for Kanye West, many layers deep.

By the end of the night, the paramilitary, never stopping despite the airless, humid night, had broken lockstep and were dancing, kicking up dust that carried across the stadium.

To be honest, it’s how I imagine a listening party with Kanye West going. He invites me over. I wait two hours after the agreed-upon time for him to arrive. Kanye being Kanye, just to irritate me, courting attention, he shows up with Marilyn Manson and DaBaby in tow — Manson who faces several assault lawsuits, DaBaby under fire for homophobic remarks at a music festival last month in Miami. They wander the house looking uncertain. Meanwhile, outside on the street, perhaps in Kanye’s mind, the house is under siege by black cars and a faceless army. The music he plays is challenging and interesting but after a while, it’s hard to pay attention to what I’m hearing, and just before it’s all over, in case I didn’t grasp Kanye’s frame of mind, he sets himself on fire.

I mean, that’s an experience, right?

Certainly, it’s a performance. But is it empty? A grand creative gesture alone can sometimes seem to be enough for Kanye — and I’m OK with that. He writes a three-story love letter to Chicago and drapes it over the old Gap on Michigan Avenue. He sells flimsy T-shirts for hundreds of dollars at a pop-up store in Northbrook and leaves you wondering about want and greed. He tours with a stage that floats over the audience but leaves himself mostly in the dark. You imagine no one is telling him what is and what is not a smart idea, and so the man is failing and succeeding in public, all the time. And it’s exciting. And annoying. How was “Donda”? The album? Dark, kind of grim, not all that catchy, full of flotsam and full of transcendence. But you probably had to be there.

This story was originally published in the Chicago Tribune on Aug. 27, 2021.

-

He joked on TikTok about dinosaur bones found on an Illinois farm. Then thousands of people started to believe him.

By Christopher Borrelli

Chicago TribuneRyan “Merf” Murphy, 42, from central Illinois, unemployed, divorced, with time on his hands, had a good idea one day that kind of got out of hand. Still, he meant well. A year ago, not long after the pandemic lockdowns began, like many, he found himself hooked on the social media app TikTok. He watched more videos than he posted, and when he posted, it was nothing special: “Sleepy” Joe Biden memes, George Carlin jokes, thoughts on cancel culture; his most popular post (45,000 views) was a clip of Ruth Bader Ginsburg explaining to Stephen Colbert why a hotdog qualified as a sandwich.

Then last month, he stumbled on a good story.

This story you’re reading is about that story, because, for a time, I wanted to believe it.

So did a lot of others.

Around Father’s Day, Merf — which is what he prefers being called — recorded a video of himself while he was driving. The news was too big to pull over or change into something more formal. He needed to get this out now. He wore a Nintendo 64 T-shirt he bought at JC Penny that afternoon and spoke breathlessly, relaying the amazing nugget of information he just learned: A local farmer in his small town was having a fuel tank removed, the backhoe struck something large, nobody knew what, a large leg bone of some sort. So “some people from California,” archaeologists, flew in, took a look and decided it was a dinosaur bone. Indeed, the largest dinosaur tibia ever discovered. Merf said the archaeologists were planning on an excavation of the farm and expected to erect an observation tent.

It was all pretty exciting.

“The biggest shindig our little town has ever had,” he said.

Merf lives in Sherman (pop. 4,549), just north of Springfield. He left that part out of the first video. He also left it out of the next several videos he posted about the bone. In the videos, he was earnest and big-hearted, almost Muppet-like. You liked him. You suspected he’s getting some of the facts wrong, but it was easy to give him a break because, well, he was excited, he was not a scientist, he wore a Nintendo shirt on a weekday and said official sounding things with the shaky authority of the recently deputized. He also peppered each update about the dig with fresh details: Local police wanted him to stay quiet, he was trying to get media credentials so he could ask more questions, the University of California and “Bureau of Land Management” were here with “ground penetrating radar,” trying to determine the size of the excavation site. A week after the initial video, he posted himself standing at dusk beside an open field. You couldn’t really see what was going on behind him. But it looked like something big was happening. The Prairie Research Institute at the University of Illinois were now in control, he said. For the next update, shot in daylight, there were even backhoes.